My district, like so many others, uses Fountas and Pinnell’s Benchmark Assessment System (BAS) as the primary measure of student reading progress. But if you’ve had doubts about the assessment and the ways BAS data is often used, you’re on to something…

Limited materials

An F&P Benchmark Assessment System kit provides us with only two books (one fiction and one nonfiction) for each reading level, so we end up using the books over and over again. We see the problem with these limited materials when struggling readers memorize the predictable texts or get stuck because they lack the background knowledge required by the two books at a particular level.

Heinemann has issued three editions of the assessment but has yet to produce any additional texts. Providing more assessment books is challenging because the texts are not authentic, but rather purpose-written assessment materials. Making more books available at a given level would call attention to leveling inconsistencies in the existing materials.

Leveling inconsistencies

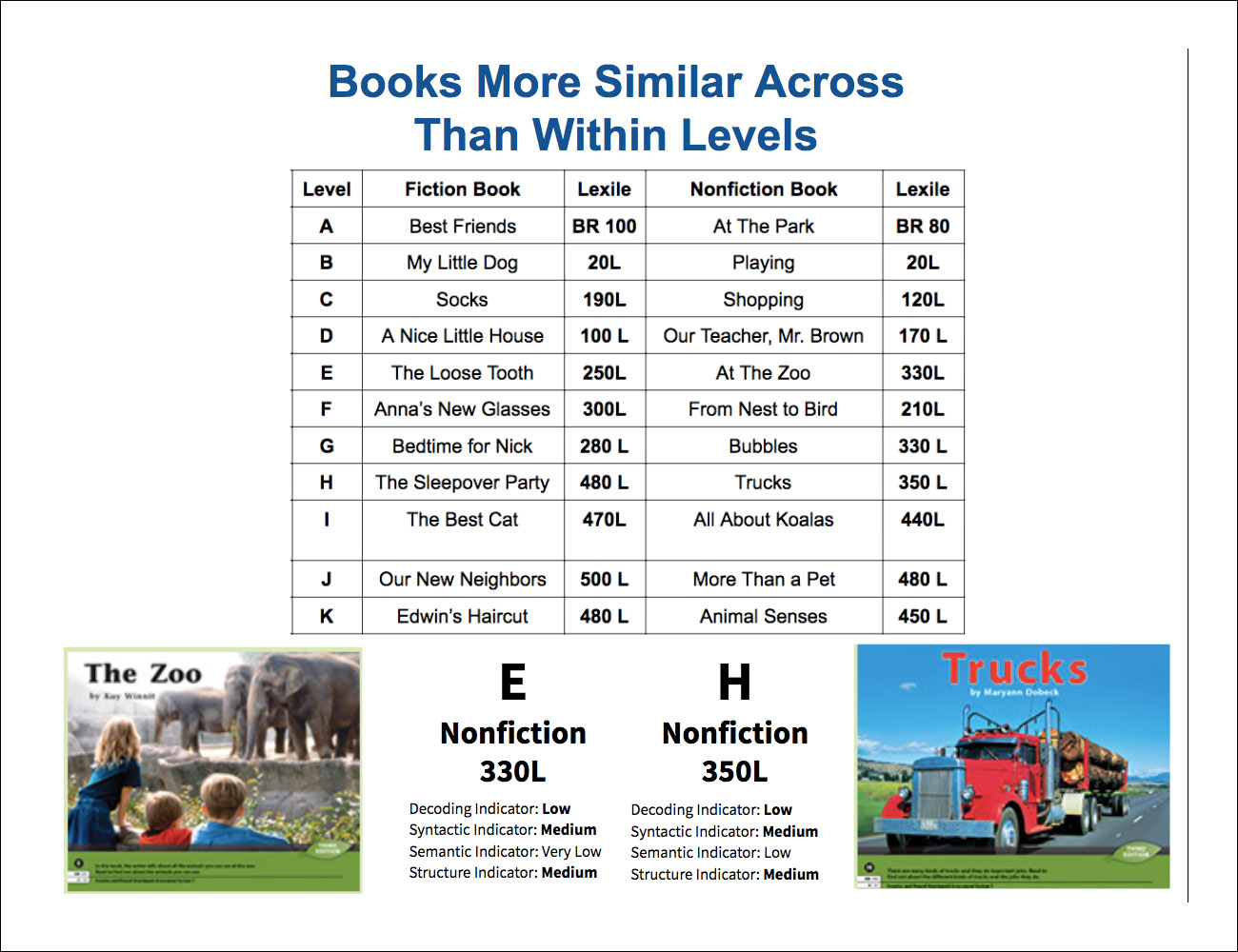

Most of us instinctively know the books in BAS are not consistent at a given level and not progressively difficult across levels. In fact, we select strategically from the book choices. I’ve heard colleagues say, “I use the Loose Tooth book because it’s a lot easier than the one about the zoo.” (both Level E) or “I skip G and go straight to H.”

The Common Core recommends that we use objective measures (Lexile, Dale-Chall, and Flesch-Kincaid are cited in CCSS Appendix A ) to evaluate text complexity. Due to lack of transparency about its formula, the F&P leveling system is notably absent in CCSS recommendations.

Lexile, cited repeatedly in CCSS appendices, analyzes written text and the features that make it objectively complex, such as decodability, sentence length, word choice. According to Lexile, the BAS Level E book At the Zoo is more similar to the Level H book Trucks than to the companion Level E book provided in the assessment kit. An objective leveling system confirms our own hunches about the books.

Selecting the BAS book The Zoo may lead us to believe that a student reads at Level E, but a closer look reveals that the same child might do just as well reading the Level H book, Trucks. These designations can mean the difference between a student being “at grade level” or “below grade level” and can impact the perception of a student’s ability, both for the student and for the teacher.

Time spent on the wrong things

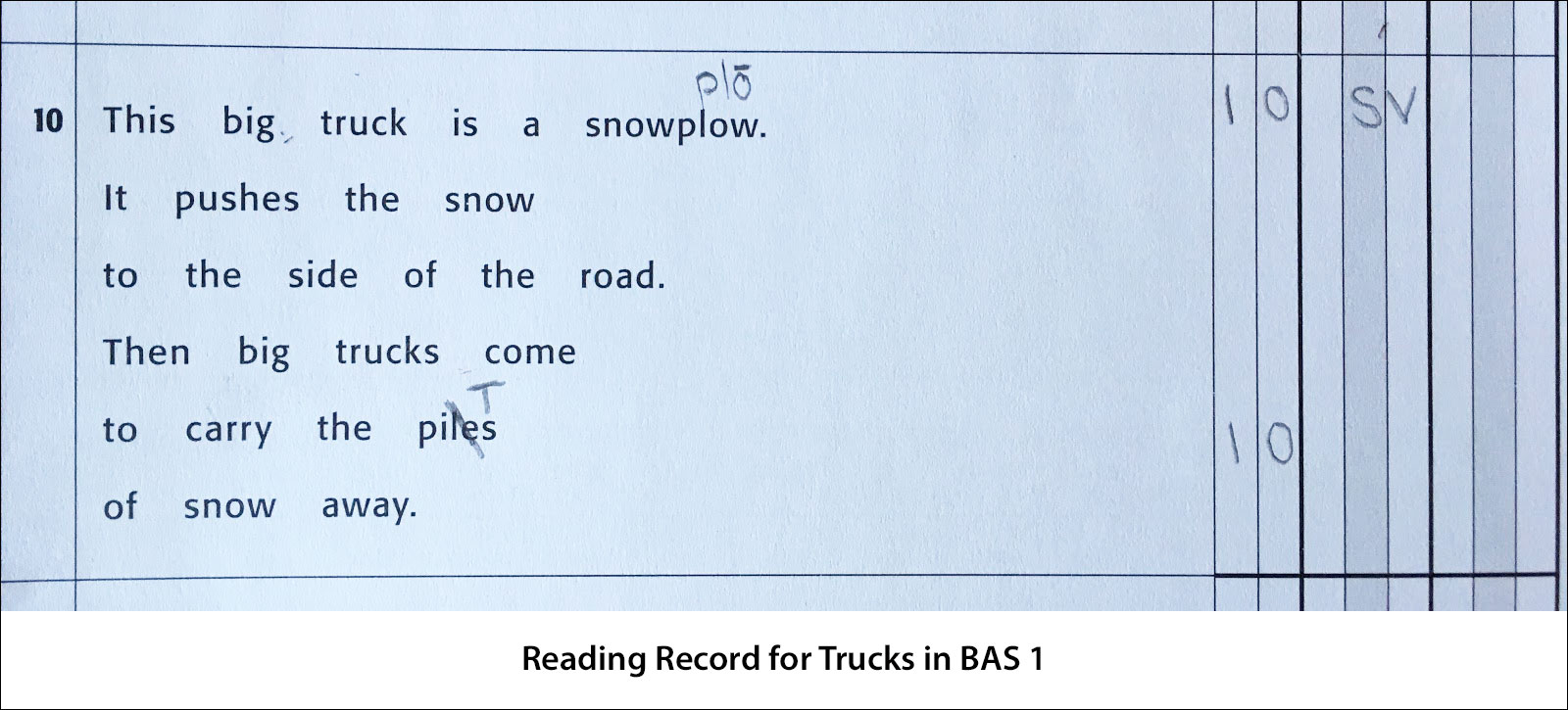

While assessing using BAS, we listen to a student read and take ”Reading Records” that we’re later expected to analyze in order to determine which of three sources of information – meaning, syntax, visual – the child used for word identification. This attention to the disproven three-cueing theory diverts our attention from the fact that an error is simply evidence that the child was unable to apply phonics to accurately read the word.

“Although oral-passage reading rate and accuracy are good measures of overall reading ability because they measure word-recognition speed and accuracy, the classification of ’miscues’ is unreliable, invalid, and a waste of the teacher’s time.”

Assessing students with BAS takes approximately 20 minutes per student, but more reliable oral reading fluency assessments take just 1 minute.

“While there are other issues to consider in terms of establishing instructional reading levels, in terms of reliability, it may make more sense to focus on more technically sound procedures available. It may be surprising to many teachers that some of the most valid and reliable measures of a student’s overall reading level include simple measures of word-recognition accuracy and speed, in and out of context (Rasinski, 2000; Torgesen, Wagner, Rashotte, Burgess, & Hecht, 1997). “

— Toward the Peaceful Coexistence of Test Developers, Policy Makers, and Teachers

Listening to students read is important for many reasons, but the books and scoring sheets provided in the BAS are not worthy of the time we’re asked to devote to them.

“Typical” students?

According to Heinemann, the Benchmark Assessment System was field-tested on “typical students,” but they included in their study only proficient English students who were already reading at grade level (and very few of them at that!) By excluding diverse learners from their study, Heinemann ignored the demographics of our classrooms and missed important factors in determining text difficulty.

The books in the assessment represent experiences typical of middle class children (eg. sleepovers and trips to the farm). Pictures in the books allow some students to cue for words (eg. climbing and snow plow), while students without that background knowledge and vocabulary must sound the words out.

The book Trucks is not a good indicator of whether an English-learner will be able to read other books labeled H by Fountas and Pinnell because it is written in present tense and is more decodable (despite snow plow!), even when compared to the other BAS Level H book, which includes tricky-to-decode irregular past-tense verbs.

“Educators are on shaky ground when a test is used in a way or for a purpose other than that for which it was intended. If a test has been developed specifically for a certain population (eg. preschool students, native English speakers) then it is imperative that the test be used solely for those it was designed to assess.”

— Toward the Peaceful Coexistence of Test Developers, Policy Makers, and Teachers

Contradictions between the authors and their product

Say we were to use the assessment only on proficient English speakers who are reading at grade level and we ignored the miscue analysis, could BAS work then?

Well, work to do what?

Attempting to use the data collected from BAS has led many of us to make instructional decisions Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell have spoken against:

| What BAS Data Tells Us: | What Fountas and Pinnell Say: |

|---|---|

| “He reads at level H.” | “The truth is that children can read books on a wide variety of levels, and in fact, they experience many different levels of books across the day.” |

| A child who reads a Level G book about bubbles during the assessment will be able to read Level G books about polar bears, friendship, and transportation. | “… we have decades of research that demonstrates the extent to which students’ vocabulary knowledge relates to their reading comprehension.” |

| If a child does well on one level, she should be assessed on the next. | “A gradient is not a precise sequence through which all students move. […] You may want to skip a level if you feel the students need even more challenge.” |

| It’s important that a student moves up levels over time. | “The point is not simply to ‘move up’ levels but to increase their breadth of reading by applying their strategies to many different kinds of texts.” |

| After each student’s reading level has been determined, students of like levels should be grouped together. | “A gradient is not and was never intended to be a way to categorize or label students, whose background experiences and rate of progress will vary widely. We have never written about leveling students.” |

| A student’s reading level should be communicated to the child so she can select “just right books.” | “We certainly never intended that children focus on a label for themselves in choosing books in classroom libraries. Classroom libraries need to be inviting places where children are drawn to topics and genres and authors and illustrators that they love. And while students are choosing books that interest them, the teacher is there to help them learn how to make good choices so the books they select are ones that they can read and enjoy. If a child chooses a book that is too hard for them to read, they may stretch themselves and enjoy that book for a period of time.” |

| The data from the assessment should be used to determine what leveled books are needed in the classroom library and which students should read which books. | “Organizing books by level does not help students engage with books and pursue their own interests.” |

Fountas and Pinnell have stated, repeatedly, that a leveling system is simply a tool for a teacher to use to match students with books. But district administrators love the assessment because it generates data that seems easy to understand (“a Level H reader is more skilled than a Level E reader”) and appears actionable (“Label and level your library and have students pick from the right bins.”)

Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell knew that reading one Level E book does not mean that the child will be able to read other books at the level equally well, and yet their names are on an assessment that sells that myth.

As teachers, we are required to spend valuable time administering this poorly constructed assessment on students for whom it was not designed, and to use the data in ways that limit student choice and even limit their access to grade-level content. It’s time for us to insist on being provided more reliable assessments and being given the flexibility to use more authentic methods for matching our diverse learners with texts they can read.

For more from Fountas and Pinnell:

- Fountas and Pinnell Say Librarians Should Guide Readers by Interest, Not Level

- Leveled Books K-8: Matching Texts to Readers for Effective Teaching (Irene C. Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell, 2006)