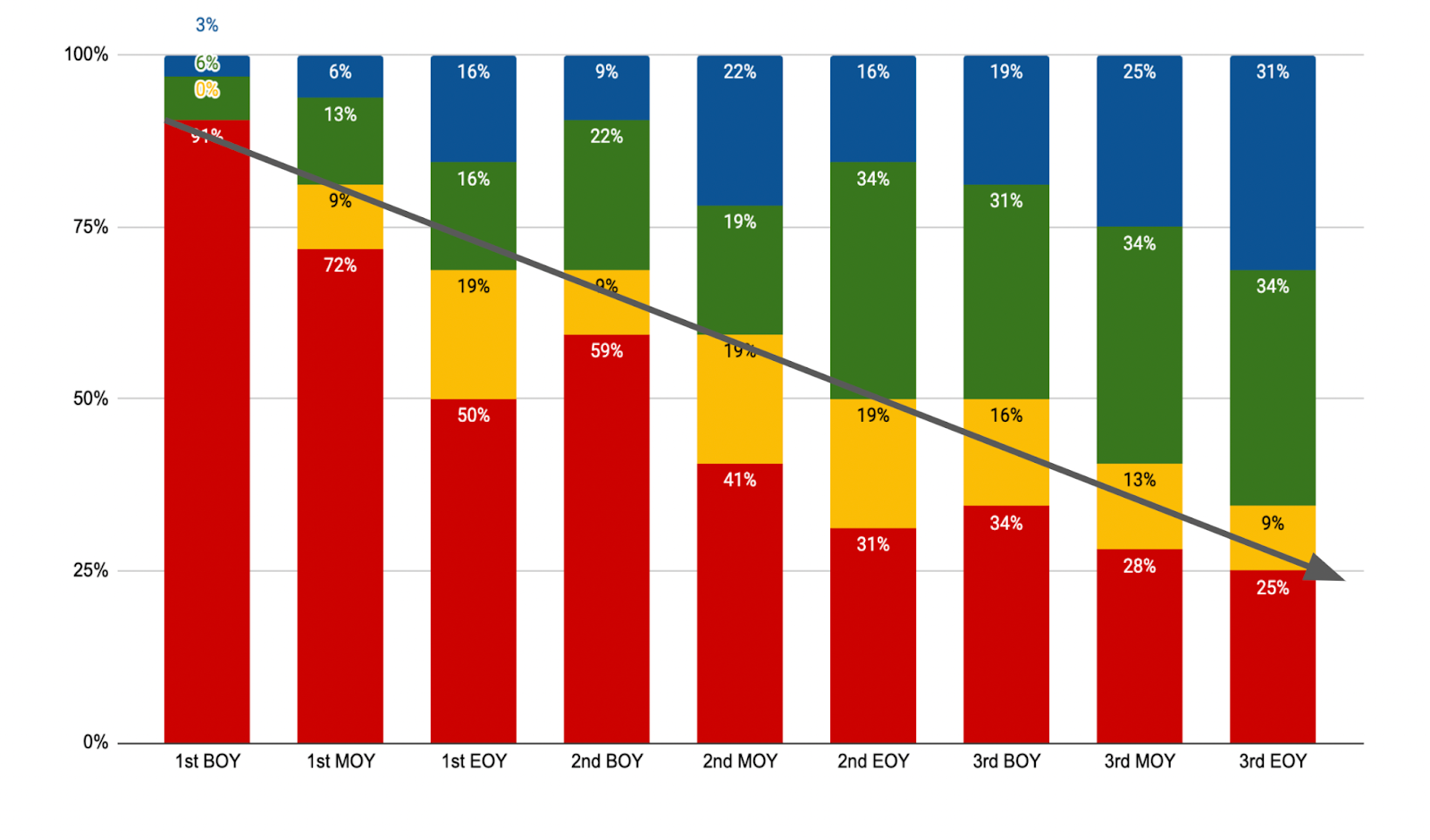

Even though I know the numbers represent real children — kids who are on a different trajectory because they learned to read at our school — the graph doesn’t reflect how it’s felt to do this work. The reality is so much more complicated than that slide suggests. But when my principal and I display it, at an upcoming conference, we won’t have the time to talk about how bumpy things have felt.

We’ll present our plans and their impact. We’ll stick to the topics within our locus of control and examine the evidence that shows we’re making a difference. We’ll explain that the graph captures only the students who have been in the cohort all three years and we won’t focus on the fact that many students have come and gone. (Our school is next to a transitional housing shelter and so the rateThe speed at which a person reads.

of transience is high.) We’ll celebrate the number of students who no longer need intensive interventionAdditional small group or individualized instruction that is tailored to children's needs so they can make progress and be on track to meet grade-level learning goals.

, but we won’t talk about the gap between not being at risk of reading failure and grade-level proficiency.

On the graph, our progress looks steady, confident, and inevitable, but that’s not how school improvement feels.

Despite the difficulties

We have plans, but executing them is more complicated than I’m ever prepared for. We improvise, make the best of things, work with what we’ve got… we do everything we can to try and make a few things better while working within an educational system that is fundamentally broken.

I don’t want to present our school as if it’s a tidy success story because I spend a good portion of the time not feeling very successful. I fret about the kids who are slipping through the cracks and the teachers who need and deserve more help than I can give. I feel exhausted when looking at how far we have to go to reach our goals and I’m terrified that not only will this work never be done, even maintaining our gains will be a challenge. Every spring, when we scrounge together short-term grants to pay for necessities, we see how easily what we’ve built can crumble.

My school is doing well despite the challenges that seem near-universal in high-poverty urban schools; chronic absenteeism, classroom vacancies, budget cuts, insufficient planning and training time for teachers.

We have a strong staff committed to ensuring the success of our students, so our problems are less crippling than neighboring schools. But it’s hard. We focus on literacy instruction despite the incessant distractions and many reasons to give up.

We persist

I’m proud of what we’ve done at my school, but I feel conflicted about whether and how we should share our progress. I’m confident that I’m fulfilling my life’s purpose, but there are so many days in which I am bone-achingly tired, I can’t possibly sell other people on this work.

Years ago, I wanted my school to be a proof-point (opens in a new window) for the power of evidence-based reading instruction. I thought that my coachingA professional development process of supporting teachers in implementing new classroom practices by providing new content and information, modeling related teaching strategies, and offering ongoing feedback as teachers master new practices.

there could be a short-term job. That seems laughable now. I still believe we need bright spots in the field, proof that school improvement is possible. We need opportunities for committed educators to learn from each other. But now I have a different, possibly conflicting hope.

I want to shine a light on the barriers that make this work so unbelievably hard. I want policy-makers, researchers, philanthropists, advocates, and changemakers to see our struggles, to study the challenges we’re facing, and to work with us to find solutions. This work is too hard to do alone.

To get reading right

I worry that if people think that my school (or any school) can raise student achievement despite the current dysfunction of our educational system, they will be less inclined to fix the problems that stymie progress and threaten our collapse.

Improving literacy rates on a large scale will require solving the problems that make working in schools like mine so challenging. We can’t get instruction right within our classrooms without addressing some of the problems outside of them.