Taking some liberty with Margaret Wise Brown’s,

The Important Book:

The most important thing about the spelling system of English is that it makes sense.

It is logical.

It is learnable.

It is critical to both reading and writing processes.

But the most important thing about the spelling system of English is that it makes sense.

In whatever capacity they work with students, educators whose responsibility it is to facilitate the acquisition of literacy and language — classroom teachers, speech and language specialists, special education teachers, administrators — may benefit from an awareness of this reconceptualization of spelling and its implications for learning.

At some time in our lives most of us have probably found ourselves muttering something like, “Why don’t we just spell words the way they sound?” In a variety of ways, students — adults as well as children — ask us this question as well. At first glance, it does seem to make sense to establish a more consistent symbol-sound relationship. For example, instead of the spellings in the left-hand column, we could have those on the right:

define | dufin |

definition | defunIshun |

courage | keruj |

courageous | kuraijus |

compete | kumpeet |

competition | komputIshun |

punish | punnIsh |

punitive | pewnutIv |

The spelling-meaning connection

In an interesting historical twist of fate, however, the English spelling system has developed in such a way that words that are related in meaning are often related in spelling as well, despite changes in sound — the spelling-meaning connection, I call it. Thus define/definition share the common spelling defin- and compete/competition share the common spelling compet-, despite differences in the pronunciation of those common letters. If we opted for letter-sound simplicity, we would lose the visual similarity among such words.

The fact that words similar in meaning tend to be spelled similarly is also an advantage when we encounter unfamiliar words in print, which in turn can support our vocabulary development. In fact, for most students beginning in the late intermediate grades, spelling and vocabulary can become two sides of the same instructional coin. Students can begin to explore this relationship when teachers help them understand why crumb is spelled with a b at the end (it is related to crumble, in which the b is pronounced) and why sign is spelled with a g (it is related to signal, in which the g is pronounced). Why isn’t the short “e” sound in pleasant just spelled with an e? Because it is related to pleasing. For students who write compisition for composition and prohabition for prohibition, point out the related words compose and prohibit, talk about how they are related in meaning to composition and prohibition, and note that, because of this, their pronunciation can be a clue to remembering how to spell composition and prohibition.

Once students are aware of and understand how the spelling-meaning connection works in known words, we can reinforce spelling while expanding vocabulary in the following way: The student who spells mental as mentle may be shown the unfamiliar word mentality. Because the stress shifts to the second syllable in mentality (menTALity), the sound and its spelling now become clear. Importantly, however, the student has also learned a new word — mentality — because he’s learned that words related in spelling are often related in meaning. Quite simply, students who know the meaning of mental can learn the meaning of mentality — while clearing up the spelling of mental in the process.

One more example of the spelling-meaning connection at work: Which spelling is correct in the following sentence: “He was alledged/alleged to have stolen valuable information”? The trouble spot in the word is the /j/ sound, which can be spelled different ways. If you think of the related word allegation, however, all doubt is removed. Allegation is related in meaning to alleged, and because words related in meaning are also often related in spelling as well, allegation provides the clue to the spelling of the /j/ sound: it is g and not dg.

Exploring the balance

We can describe the process of learning about the English spelling system as a developmental exploration of the balance between sound and meaning. Learners begin with the expectation that spelling represents sound and grow toward the understanding that spelling also represents meaning. The box on page 12 illustrates in broad strokes the outlines of a scope and sequence for spelling instruction expressed as a function of developmental level. This scope and sequence is based on extensive research in the development of word knowledge in reading and spelling; the labels for the type of word knowledge expressed as a function of developmental level of literacy are derived from Edmund Henderson’s landmark work in developmental spelling. Henderson was the mentor at the University of Virginia for many of those, myself included, who researched developmental spelling and word knowledge.

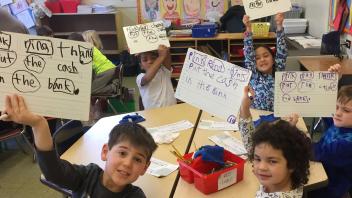

In order to engage students in active, purposeful exploration of words so that they attend to the critical features that determine spelling/sound relationships, we encourage the use of word categorization or word sort activities. In word sorts, each word is written on a separate card (3-by-5 cards cut into fourths work well) so that the words can be physically manipulated into different categories. Word sorts engage learners in comparing and contrasting words that follow a particular sound or meaning pattern with those that don’t. For example, younger children can compare words that end in e with those that don’t (cap vs. cape) and discuss what that tells them about the vowel sounds within the words. A little later, they can explore words that double final consonants when adding inflectional endings with those that don’t (hopping vs. raining). Much later still, they can compare and contrast words that end in –able and –ible (readable vs. visible).

In addition to word sorts, students should also be engaged in writing sorts in which one student calls out the words to another student who writes each word in the appropriate category. Word sorts and writing sorts require the type of discrimination that strengthens connections between visual or spelling patterns, sound patterns, and meaning patterns.

Dylan and Delayne — second-graders

Let’s consider how an analysis of error patterns helps to determine developmental level and thus instructional focus. Following are examples from a Qualitative Spelling Inventory for second-graders Dylan and Delayne at the beginning of the school year:

Dylan | Delayne | |

|---|---|---|

bed | bad | bed |

ship | sep | ship |

drive | jriv | drive |

bump | bop | bump |

when | wn | wen |

train | chran | trane |

float | fot | flote |

There are qualitative differences between Dylan and Delayne’s levels of spelling knowledge. Dylan is an alphabetic speller; he can quite reliably discern individual sounds within syllables. He evidences knowledge of single consonant spellings (b, d, s, p, v, n, f) but is not firm on the spelling of consonant blends (JR IV, CH RAN) and short vowels. His selection of letters to represent the short vowels, however, is well-motivated: He has selected the letter whose name is closest based on point of articulation, thus the selection of a for short “e” (BAD) and e for short “I” (SEP).

Delayne has moved into within-word pattern. She is stable on the representation of consonant digraphs, blends, and short vowels, but is just beginning to apply understanding of long-vowel pattern as evidenced in her spelling of TRANE and FLOTE. This type of error shows that Delayne has moved beyond a linear conception of spelling and is able to think “back and forth” simultaneously within a word. She is able to embrace the notion of pattern : A group or chunk of letters that correspond in a systematic way to sound. Once learners attain this understanding, they are ready to explore the various ways in which vowel sounds are represented within single syllables.

Dylan can focus on and learn the conventional spellings for short vowels by working with a word family in which the different short vowels are substituted — for example, hat / hit / hot. A little later, consonant blends and digraphs can be added to these simpler patterns for comparison and contrast. Delayne would benefit from the following type of word sort to discriminate among different vowel spelling patterns:

Key Words | ||

|---|---|---|

make | day | gain |

flake | say | train |

stage | pay | brain |

chase | stay | chain |

tale | clay | |

These types of examination across spelling patterns help Delayne learn about the role of position in spelling (–ay represents “long a” at the end of words but never within a single syllable) and reinforce memory for the spelling of particular words.

Luis and Gina — fifth-graders

Following are examples from a Qualitative Spelling Inventory for fifth-graders Luis and Gina:

Luis | Gina | |

|---|---|---|

trapped | trapped | trapped |

battle | battel | battle |

lesson | lesin | lesson |

pennies | pennys | pennies |

fraction | fracshun | fraction |

confusion | confushion | confusion |

discovery | discovary | discovery |

resident | resadint | resadent |

visible | vizabul | visable |

Luis is a solid syllables and affixes speller. He will continue to explore what occurs at the juncture of syllables (LESIN) through comparing and contrasting syllable patterns and the spelling of common suffixes (-tion, -sion; changing y to i). Gina is a derivational-relations speller. She will continue to explore affixation as it applies to base words but also to word roots. The following two sorts illustrate the type of patterns Luis may explore:

Key Words | |

|---|---|

tablet | baby |

napkin | human |

happen | music |

winter | fever |

foggy | silent |

tennis | duty |

sudden | writer |

fossil | rival |

Through this type of sort, Luis will develop the understanding that, for two-syllable words, a syllable containing a short vowel is usually followed by two consonants; a syllable containing a long vowel is usually followed by one consonant.

Key Words | ||

|---|---|---|

hurry | hurries | hurried |

party | parties | partied |

empty | empties | emptied |

baby | babies | babied |

reply | replies | replied |

supply | supplies | supplied |

cry | cries | cried |

carry | carries | carried |

fry | fries | fried |

Luis will discover that, regardless of the sound that y represents, when it occurs at the end of a word and is followed by a suffix that begins with a vowel, the y is changed to i.

The following sort illustrates the type of exploration that will help Gina attend to the spelling and meaning relationships that preserve the visual similarity between related words:

Key Words | |

|---|---|

invite | invitation |

define | definition |

reside | resident |

deprive | deprivation |

admire | admiration |

inspire | inspiration |

Gina will learn that the stressed vowel in the base word will provide a clue to the spelling of the reduced vowel sound in the derived word.

Later on in her word study, the following sort will help Gina learn what determines whether –able or –ible is appropriate:

Key Words | |

|---|---|

breakable | credible |

dependable | audible |

passable | edible |

agreeable | feasible |

predictable | compatible |

acceptable | possible |

Usually, –able is added to a base word (for example, break and predict); –ible is added to a word root (cred, aud, poss).

Though I have highlighted word sorts here because of their effectiveness, I would like to emphasize that effective and enjoyable spelling or word study also includes exploration of synonyms, antonyms, acronyms, similes, metaphors, casting words in analogical relationships, and exploring word histories.

Orthography in support of literacy

At present, developmental spelling research is helping us understand how students’ knowledge of the spelling of words — their orthographic structure — can support students’ ability to read words. We now understand that a common core of word or orthographic knowledge underlies students’ ability to read and spell words. Assessing this knowledge through a well-constructed inventory of spelling knowledge, as well as examining the errors in students’ writing, provides teachers insight into this core knowledge and helps them determine where each of their students falls along a developmental continuum of word knowledge. This insight in turn helps teachers determine which types of word features in the scope and sequence each student should explore. In addition, developmental spelling research is helping us understand better how English-language learners are bringing knowledge of their first language to bear on their acquisition of speaking, reading, and writing in English, as well as how teachers of students with learning and hearing disabilities can guide literacy development.

This newer conceptualization of the nature, role, and learning of spelling is not widespread, but it is definitely gaining a foothold. All of us who work in some capacity with students can benefit from spreading the word as we learn ourselves how the spelling of words yields fascinating insight into their sounds, their meanings, and their histories. The system is logical, learnable, and critical to reading as well as to writing — but the most important thing is, it makes sense.

Shane Templeton is Foundation Professor of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Nevada, Reno, where he is also program coordinator for literacy studies and associate director of the Center for Learning and Literacy. A former classroom teacher at the primary and secondary levels, his research has focused on developmental word knowledge in elementary, middle, and high school students.

Reprinted with permission from The ASHA LEADER Online. Templeton, S. (2002). Spelling: Logical, Learnable-and Critical. Available from the website of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association: http://www.asha.org/Publications/leader/2002/020219/020219d.htm. All rights reserved.