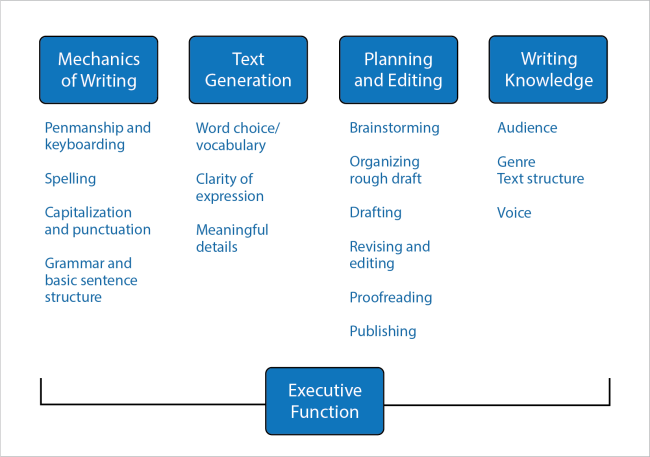

Writing is a complex process that requires a wide range of skills — basic mechanical skills; a strong vocabulary; an understanding of genre, text structure, and voice; organizational skills; and higher-order thinking.

Writing requires a wide range of skills

- basic mechanical skills (handwriting, spelling, grammar and punctuation)

- a strong vocabulary

- an understanding of genre, text structure, and voice

- organizational skills

- higher-order thinking

It’s no wonder that most students need high-quality instruction to learn how to write well! Effective writing instruction requires more than giving students time and a purpose for their writing.

We need to teach all the necessary components explicitly and systematically.

Elements of writing

Handwriting

Is penmanship really worth teaching if so many of our students will end up typing in the later grades? Yes! Learning proper letter formation helps students to distinguish between often confused letters (such as d, b, p, and q) which in turn helps them to become fluent readers. Learning to write words effortlessly can also reduce the barriers between our students’ thoughts and what they record on paper.

Explicit instruction in penmanship combined with regular practice opportunities helps ensure that almost all students develop effortless, legible handwriting. When we show students how to form letters, we need to teach them to sit up, with their feet on the floor, paper slightly slanted, and their writing utensil grasped correctly.

While some students internalize these habits without much instruction, many other children compensate for poor form with varying degrees of success. When forming letters is laborious or inefficient, students often experience difficulty recording their thoughts on the page, which ends up affecting their word choice, sentence construction, the length of their compositions, and even their willingness to write altogether.

If a child struggles with handwriting even after explicit instruction and opportunities to practice, it may be helpful to put in place instructional supports that benefit students with dysgraphia . Dysgraphia is a disorder of written expression (not simply a problem with handwriting). But some of the strategies we use for dysgraphia (e.g. using paper with raised lines) may also help students who have not been formally diagnosed with dysgraphia.

Is handwriting actually important for writing?

Joan Sedita, founder of Keys to Literacy, talks about how research shows that young students improve their writing and alphabet knowledge when they handwrite letters and words while simultaneously learning letter-sound correspondence.

Learn more

Spelling

As students begin to master phonics, we need them to apply that knowledge when they sit down to write. In the early grades students may use “approximated spelling,” recording the sounds they hear, using the phonics that they know. As students become more familiar with the written code of English, we expect that their spelling will become increasingly conventional over time.

Spelling gives us insight into our students’ phonemic awareness as they convert the sounds they hear into written words. Spelling also provides tangible evidence of the phonics students have learned from instruction and exposure. The importance of spelling for reading is summarized by Snow et al.:

“Spelling and reading build and rely on the same mental representation of a word. Knowing the spelling of a word makes the representation of it sturdy and accessible for fluent reading.” (Snow, 2005)

In other words, our students’ writing gives us a window into which words they can read effortlessly and which words may still present a decoding challenge.

Writers who must think too hard about how to spell words use up brain-space that could otherwise be used for higher-level tasks writing tasks such as organization, word choice, clarity, and voice (Singer and Bashir, 2004). Students who struggle to spell well may not employ their full vocabulary and, instead, restrict themselves to words they know how to write. Encouraging approximated spelling may temporarily help to alleviate that struggle, but it is important that students understand that conventional spelling is ultimately by far the best way to communicate with their readers.

See also: How Spelling Supports Reading.

Grammar

Grammar, like handwriting and spelling, is often given instructional short-shrift, perhaps because it’s not widely thought of as a component of progressive education or because teachers are not typically well-prepared and supported in teaching it. Providing instructional time for brainstorming ideas and generating drafts is important, but it’s also important that we teach our students to value the quality of their writing over the quantity.

Clear expression of ideas depends upon grammatical sentences. All the work that students put into brainstorming does little good if they can not then write those ideas coherently. For this reason, we need to teach our students how to construct grammatical sentences that allow them to express their ideas effectively.

At first, students will need to learn how to construct simple sentences, including word order, capitalization, and punctuation. But as they develop ideas that are increasingly complex, they need instruction to help them draft more complex sentences.

We can introduce the components of grammar and syntax (word order) during explicit instruction by using isolated examples, but we also need to show students how to tie the concepts immediately to their writing assignments.

Studies have shown that teaching grammar in isolation yields poor results, but grammar applied to the act of writing has a positive effect.

William Van Cleave, 2012

For more on teaching grammar, see the In Practice section of this module.

Genre, text structure, and organization

Before sitting down to write, students need to understand the genre in which they’ll be working. For example, when writing stories, they need to be prepared to recount the sequence of events. When expressing an opinion, students need to prepare to offer supporting details, and when describing a problem they might need to know how to structure their work with a cause followed by its effects.

Analyzing the structure of exemplar texts can support students in organizing their own thinking before writing. Studying the kinds of transitions appropriate for a particular genre — for example, understanding that “in conclusion” may be helpful for an argumentative piece but should probably not appear in a narrative — can help thoughts flow from one sentence to the next, provide structure to a paragraph, and develop a logical sequence from the start to the end of a piece.

Learn more

Vocabulary

Effective writing depends on thoughtful word choice and that, of course, depends on a writer’s vocabulary. Encouraging students to use newly acquired vocabulary in their writing can enrich the language that they use, but we need to ensure that students use words grammatically and precisely. If a student writes a sentence such as, “He disrupted the candy bar,” we can see that she understands that the word disrupt has something to do with “breaking something up,” but the nuance has been lost. When students encounter difficulty integrating new words into their oral and written vocabularies, it’s important that we seize the opportunity to reteach and deepen their understanding of the new words.

Teaching students to replace bland word choices (nice, good, fun) with more descriptive words (e.g., prompting a writer, “By nice, did you mean pleasant, kind, or agreeable?”) can help them to express their ideas more clearly. As with other components of writing instruction, it’s important to ensure that students learn to write concisely as well, so they don’t add long lists of adjectives to their writing for the sake of filling more lines. When introducing the concept “less is more,” it may be helpful to share with students not only examples and non-examples, but also quotes from professional writers who have written about high-quality writing, such as Mark Twain:

When you catch an adjective, kill it. No I don’t mean utterly, but kill most of them — then the rest will be valuable. They weaken when they are close together.

Learn more

Voice

In writing, voice conveys feelings, emotions, and the author’s perspective. The voice of a piece of writing should be appropriate for the topic, purpose, and audience of the piece, and the language can make the piece of writing effective and enjoyable to read. Even primary grade students can take pleasure in playing with voice in their writing.

Students often start out writing conversationally (like a first grader who wrote about a story, “Cowgirl Kate had a hissy fit because the horse made a mess in the house.”) or playing with word choice (like another student who accompanied her picture of racoons with the label, “I see chrash [trash] pandas when the moon comes out.”) Students who express their humor through writing will often enjoy reading their writing aloud, which can provide an opening for authentic discussions about the importance of word choice, sentence construction, and other components of effective writing.

Over the years, students must learn how to adjust their writing to capture a voice appropriate for their intended audience and genre. By explicitly teaching text structure and organization, vocabulary, grammar, and the other foundational skills necessary for fluent writing, we can ensure that students learn to write effectively for a variety of purposes.

Writing poems

In Houston, Lynn Reichle and her second-grade students go on a writing adventure called the Writers’ Workshop.