For some children, learning to read and write occurs almost effortlessly. For others, every literacy milestone is a monumental struggle. Understanding how and why children learn to read is critical for planning effective instruction.

Researchers design and test models of reading to provide an explanation for how reading develops. These models shape educators’ beliefs and guide how to plan classroom instruction and intervention. Cognitive scientist Dr. Mark Seidenberg (2017) argues that how students are taught to read should be based on rigorous research evidence not on teacher intuition or long-held teaching practices.

The simple view of reading

Let’s look at one model of reading comprehension that has been widely tested and accepted among reading researchers: the simple view of reading (SVR). Phil Gough and William Tunmer (1986) developed an elegant concise theory to describe what must happen to comprehend print. They described the act of reading comprehension as the product of two cognitive skills:

Decoding x Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension.

In the SVR model, good reading comprehension requires the interaction of two broad sets of abilities: decoding (D) or word recognition and language comprehension (LC). If one or both sides of the equation are missing or diminished, then reading comprehension will suffer or even be absent.

So, if you add 0’s (skill is not present) and 1’s (skill IS present) to the equation:

- 1 (D) X 1 (LC) = 1 (good reading comprehension)

- 0 (D) X 1 (LC) = 0 (poor reading comprehension because of word recognition deficits, often seen with dyslexia)

- 1 (D) X 0 (LC) = 0 (poor reading comprehension because of oral language comprehension deficits, often seen with hyperlexia)

For young readers, decoding is a better predictor of their reading success, but once children master decoding and get older, the skills under language comprehension become more important for reading success.

Let’s look at a list of the skills included within the SVR framework:

| Word recognition under SVR includes: | Language comprehension under SVR includes: |

|---|---|

| Accurate and quick letter name and letter sound knowledge | Vocabulary knowledge |

| Phonological and phonemic awareness | Background knowledge |

| Phonics and decoding skills | Sentence (syntactic) comprehension |

| Automatic recognition of common high-frequency words | Understanding figurative language, such as metaphors, similes, and idioms |

| The ability to read common phonetically irregular words |

Using the SVR in instruction

The SVR equation helps educators to pinpoint students’ strengths and weak areas in reading, and identify three different types of reading difficulties a student may have: dyslexia, hyperlexia, and garden variety poor reading (mixed types). Students who have poor skills on both sides of the equation, or what David Kilpatrick calls “mixed types”, are the most common type of reading difficulty in U.S. schools. Students with dyslexia or poor word reading and adequate language comprehension are less common. Very few students are what some teachers call “word callers” or hyperlexic.

Understanding the different reader profiles is useful for planning classroom instruction and support.

The SVR predicts 4 different types of reading

Voices from the field: Linda Farrell

Reading expert Linda Farrell explains the simple view of reading, in this clip from our Looking at Reading Interventions series.

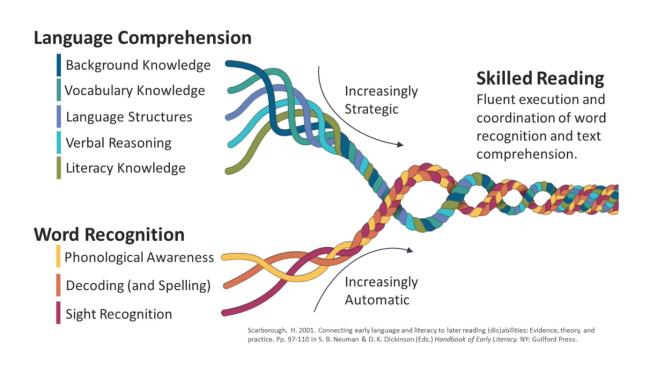

Scarborough’s Reading Rope

As we learn more about the simple view of reading, we discover that it’s not actually so simple. Each part of the simple view equation represents a set of specific sub-skills or factors related to reading. Hollis Scarborough’s popular infographic, the “Reading Rope” (2001) helps educators understand how the SVR sub-skills combine and intertwine to support learning to read.

Some educators may confuse Scarborough’s infographic as a separate model from the simple view of reading, but essentially it shows us visually what’s most important for teaching reading. The reading rope complements and adds some sub-skills, but it is not separate from the simple view of reading.

Modified from Scarborough, H.S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, Theory, and Practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy. New York: Guilford Press.

Expanding the simple view of reading

Although the simple view addresses the cognitive factors in reading, some researchers have expanded upon the SVR model to include school, home, and psychological factors that influence reading. Let’s look at two promising models: the componential model and the active view of reading.

Componential Model

Aaron and Joshi (2000) expanded the simple view of reading into the componential model of reading. The componential model builds upon the SVR and has three areas: cognitive, psychological, and ecological factors for reading. The componential model encourages educators to go beyond cognitive skills and to consider school and home factors when planning instruction.

Componential Model (Aaron & Joshi, 2000); Aaron, Joshi, & Quatroche, 2008)

Active View of Reading

Nell Duke and Kelly Cartwright (2021) propose that not all reading problems fall neatly under decoding or language comprehension. They argue that some areas such as vocabulary, morphology (meaningful word parts), and fluency influence both sides of the SVR equation and cannot be adequately explained by the simple view of reading.

This active view of reading model expands the simple view to include a bridge between decoding and language comprehension and adds self-regulation skills a reader uses to monitor their reading. Self-regulation of reading means the reader uses neurocognitive skills to attend, plan, organize, strategize, and remember how to read a text.

Although there is research for each of this model’s individual components, the complete active view model has not been rigorously tested yet. You can read the complete article about the active view of reading, The Science of Reading Progresses: Communicating Advances Beyond the Simple View of Reading

The Active View of Reading © 2021 Nell K. Duke & Kelly B. Cartwright. Reading Research Quarterly published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of International Literacy Association.

Other models of reading

Dual-Route Theory

Another proposed model is the dual-route theory, which suggests that there are two pathways in the brain for word reading: a phonological route and an orthographic route. The phonological route involves applying letter-sound relationships to sound out unfamiliar words. The orthographic route identifies a familiar word by its spelling patterns. Some of the researchers who have contributed to our understanding of dual route theories are Max Coltheart, Uta Frith, Philip Seymour, and David Share.

Construction-Integration Model (CIM)

In the construction-integration model (CIM) described by Dr. Walter Kinstch (1988), readers assemble meaning from texts by building a mental blueprint of the text. CIM assumes that reading comprehension must include factors such as:

- activating prior knowledge,

- generating inferences,

- resolving inconsistencies, and

- integrating information across sentences and paragraphs.

According to the CIM model, reading comprehension happens in two stages. First readers generate a set of propositions or ideas about the text during reading. These initial interpretations form a networked blueprint or mental map. This first stage relies heavily on the reader’s prior knowledge and expectations about the text.

In the second stage, the reader must choose the best interpretation that makes the most sense based on the available evidence and context. To do this, the reader must monitor their reading and use strategies to repair it when breakdowns occur. Children evaluate and revise their thinking until they have a stable, consistent mental representation of the text. You can get an idea of how this model works below.

According to the CIM, teachers should use assessment and instruction to foster higher-order thinking skills and show children how to monitor and repair as they build a mental model of the text. This last model focuses heavily on what happens as a reader responds to a text. Unlike the earlier models, CIM thinks about reading comprehension as a process rather than a set of specific teachable sub-skills.

These are some of the current models used by researchers to explain how reading develops and the processes and skills behind learning to read and spell words.

Why these models are important

You might be thinking, “ I’m not a researcher, so why do I need to know about this?”

A basic understanding of these models is important, since they can guide our decisions about which reading programs and instructional practices are promising and are in line with how children read. We can eliminate instructional practices that lack evidence and waste precious instructional time. Finally, for teachers of struggling readers, these models provide insight into why a child might have trouble learning to read, so you can target specific assessment and intervention supports.