Introduction

By: Joan Sedita

The literature and discourse related to literacy instruction tends to focus on reading, even though writing is just as important for student literacy achievement. In addition, significant attention is paid to the multi-component nature of skilled reading, while writing tends to be referred to as a single, monolithic skill.

Much has been written about the multiplicity of skills involved in reading, beginning with the “five components” model that became popular after the 2000 report of the National Reading Panel (i.e., phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension). Levels of language skills are often referred to in terms of how they contribute to skilled reading (i.e., phonology, orthography, morphology, syntax, semantics, discourse). School assessment plans typically organize formal and informal measures around the discrete reading skills that they measure (e.g., phonemic awareness, word or passage oral reading fluency, vocabulary knowledge, sentence or passage reading comprehension). Some published reading programs focus on specific reading components by design (e.g., phonological awareness programs for young children, phonics programs for the primary grades) and core reading programs identify how discrete reading skills are addressed in daily or weekly lessons.

On the other hand, when attention is paid to writing instruction, teachers are not sure what writing instruction should include. Many educators who are knowledgeable about effective reading instruction are not able to: (1) identify the components of skilled writing, (2) explain how levels of language contribute to skilled writing, (3) identify a set of writing assessments, or (4) suggest a comprehensive curriculum for teaching writing.

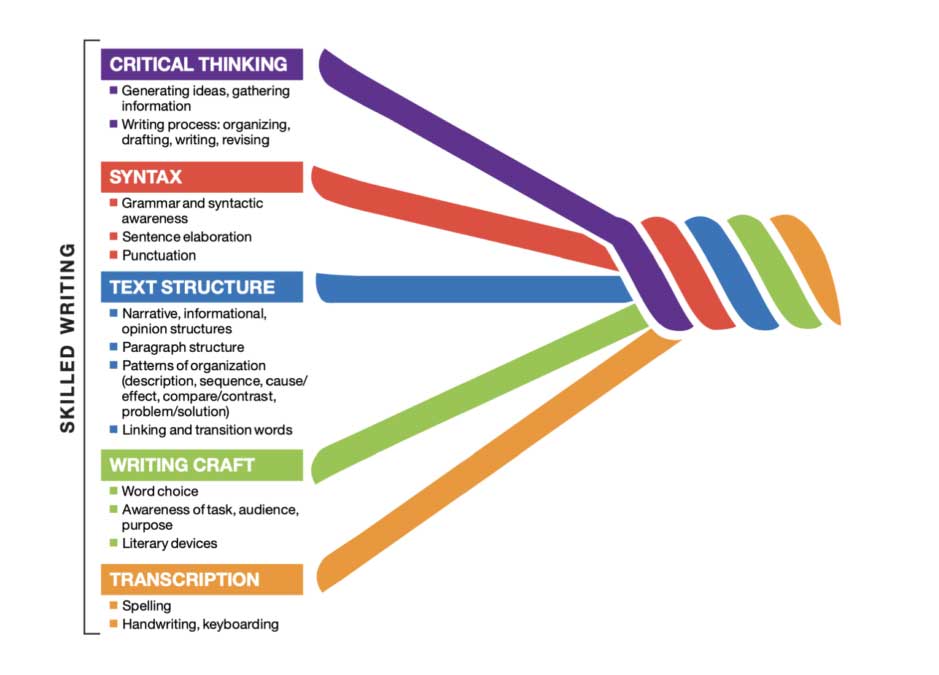

With a nod towards Hollis Scarborough’s “Reading Rope” (see Models of Reading), I’d like to suggest a model that identifies the multiple components that are necessary for skilled writing. In 2001, Scarborough published a graphic that depicts multiple components of language comprehension (i.e., background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, literacy knowledge) and word recognition (i.e., phonological awareness, decoding, sight recognition) as strands in a rope. As students develop skills in these components they become increasingly strategic and automatic in their application, leading to fluent reading comprehension.

A similar “rope” metaphor can be used to depict the many strands that contribute to fluent, skilled writing, as shown in the graphic below. It should be noted that instruction for many skills that support writing also support reading comprehension.

© 2019 Joan Sedita, Keys to Literacy. Published in The Writing Rope: A Framework for Explicit Writing Instruction in All Subjects (Brookes Publishing Company).

Produced by Reading Universe, a partnership of WETA, Barksdale Reading Institute, and First Book.

The critical thinking strand

This strand draws significantly on critical thinking and executive function skills, as well as the ability to develop background knowledge about a writing topic. It also requires an awareness of the writing process (i.e., organizing, drafting, writing, revising). Students engage in critical thinking as they think about what they want to communicate through their writing. If they are composing an informational or opinion piece, they may need to tap into comprehension skills to gather information from sources. Students benefit from explicit instruction for brainstorming strategies and skills for gathering information from written and multi-media sources, such as note taking. They also need to learn planning strategies for organizing their thoughts, including the use of prewriting graphic organizers. Students need to be metacognitive and purposeful about working recursively through the stage of the writing process, and they benefit from explicit instruction in revising and editing strategies.

The syntax strand

Individual sentences communicate ideas that add up to make meaning. Efficient processing of sentence structure is necessary for listening and reading comprehension, as well as for communicating information and ideas in writing. Syntax is the study and understanding of grammar — the system and arrangement of words, phrases and clauses that make up a sentence. Students develop syntactic awareness as they learn the correct use and relationship of words in sentences. This begins with exposure to proper English by listening to people talk and reading or listening to written text. Students benefit from explicit instruction focused on building sentence skills, including activities such as sentence elaboration and sentence combining.

Teaching sentence writing

Get the details on how to teach students to write simple sentences and more complex, expanded sentences in these multimedia skill explainers from our sister project, Reading Universe . You’ll find lesson plans, classroom video, student practice activities, assessments, and more.

Writing a simple sentence

Students need explicit instruction about the basic elements and structures of a sentence in order to build the foundational knowledge and skills needed to write effective sentences. Every simple, complete sentence must have two parts: a naming part (the subject) and an action part (the predicate).

- See the Skill Explainer: Writing a Simple Sentence

Sentence expansion

Once your students can write a simple sentence with a subject and predicate, they are ready to learn how to expand on their sentences and communicate more complex ideas. Basic sentence expansion activities use the question words who, what, when, where, why, and how.

- See the Skill Explainer: Sentence Expansion

The text structure strand

Text structure is unique to written language, and awareness of several levels of text structure supports both writing and reading comprehension. Students benefit from explicit instruction in several levels of text structure:

- Narrative, informational, and opinion text structure: knowledge of the different organization structures for these three types of writing, including the use of introductions, body development, and conclusions.

- Paragraph structure: understanding that written paragraphs are used to “chunk” text into manageable units that are organized around a central idea and supporting details.

- Patterns of organization: understanding that sentences and paragraphs can be organized to convey a specific purpose including description, sequence, cause and effect, compare and contrast, problem and solution.

- Linking and transition words or phrases: ability to use words or phrases to link sentences, paragraphs or sections of text — including knowledge of transitions associated with specific patterns of organization.

The writing craft strand

This strand addresses skills and strategies often referred to as “writers’ craft” or “writers’ moves.” Students benefit from explicit instruction in the following:

- Word choice: purposeful use of specific vocabulary, word placement and dialogue to convey meaning and create an effect on the reader.

- Awareness of task, audience, purpose: being mindful of these elements in order to influence decisions about word choice, tone, length and style of a writing piece.

- Literary devices: understanding and use of common literary elements (e.g., plot, setting, narrative, characters, theme) and literary techniques (e.g., imagery, personification, figurative language, alliteration, allegory, irony).

The transcription strand

This strand addresses spelling and handwriting (or keyboarding) skills. They are basic skills that are needed to transcribe the words a writer wants to put into writing. Just as developing fluency with decoding skills enables students to focus on making meaning while reading, the sooner students become automatic and fluent with spelling and handwriting, the sooner they will be able to focus their attention on the other strands of the writing rope. During the primary grades, students benefit from explicit instruction in spelling (e.g., phonics), and handwriting or keyboarding.

Guidelines for Writing Instruction

These guidelines for K-12 instruction in each of the five strands suggest grade ranges according to three stages: formal instruction and initial learning, refinement of instruction, and ongoing and advanced use. (Developed by Joan Sedita) Guidelines for Writing Instruction

Learn more in this blog post from Keys to Literacy: Writing Instruction Scope & Sequence

Low levels of writing proficiency

Much attention has been placed on the 2019 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) reading assessment results showing that the average reading scores in the U.S. were lower for both fourth- and eighth-grade students compared to 2017, with only 35% of fourth graders and 34% of eighth graders scoring at or above proficient. However, the most recent NAEP writing assessment results (2011) should be even more concerning: only 24% of students at both grades 8 and 12 performed at the proficient level. In reporting these NAEP scores, the following was noted:

It is clear that the ability to use written language to communicate with others — and the corresponding need for effective writing instruction and assessment — is more relevant than ever.

Yet the degree of focus placed on writing is much less than the attention paid to reading.

References

National Assessment of Educational progress. (2019). Reading assessment. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/reading/

National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2012). The nation’s report card: Writing 2011. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pubs/main2011/2012470.asp

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy (pp. 97–110). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

About the author

Joan Sedita is the founder and president of Keys to Literacy , a literacy professional development company based in Massachusetts, training teachers across the country. Joan is the author of multiple professional development programs including Keys to Beginning Reading, The Key Comprehension Routine, The Key Vocabulary Routine, Keys to Content Writing, and Keys to Early Writing.