Key Information

Focus

When To Use This Strategy

Appropriate Group Size

What is story sequence?

Story sequence is the order in which events take place in a narrative. In simplest terms, sequencing a story means identifying the main narrative components — the beginning, middle, and end—as a first step towards retelling the events of the story in logical order. Story sequencing is also a precursor for more sophisticated ways of understanding narrative text structure, such as determining cause and effect, which students will need to access more complex text. Sequencing is also an important component of problem-solving across subjects.

Why teach story sequence?

- The ability to sequence events in a text is a key comprehension strategy, especially for narrative texts.

- It enables retelling, which in turn enables summarizing.

- It promotes self-monitoring and rereading.

- The ability to place events or steps in logical order is invaluable across the curriculum, whether it’s identifying the steps for solving a math problem or the series of events that led to a turning point in history.

How to teach story sequence

Story sequencing is often introduced and practiced in the context of a whole-class read-aloud. You might choose to teach a standalone sequencing lesson or to include sequencing as part of a longer lesson leading to oral or written retelling of the story.

Read-aloud texts that work well for introducing story sequencing have straightforward narrative arcs and clear sequences of events. Sequencing can also help students make sense of more complex narrative structures, such as stories that are written out of chronological order or that include parallel accounts of the same events from more than one point of view.

There are many ways to structure a sequencing lesson, from creating an anchor chart with student input to having the students participate actively by “holding the pen” or coming to the front of the class to reorder movable pictures or sentence strips.

Watch a demonstration (grades K-1)

The teacher explains that asking students to retell stories both orally and in writing helps them structure their retells with a beginning, middle, and an end. The teacher works with students who have difficulty writing independently by having them sound out the words and at times, writes them in for students as needed. (Balanced Literacy Diet: Putting Research into Practice in the Classroom)

Watch a lesson (whole class, grade 2)

The teacher reviews sequencing with the class and guides the students through identifying the beginning, middle, and end of a whole-class read-aloud of How the Grinch Stole Christmas while creating an anchor chart. The lesson uses pair conversations to build student engagement and accountability.

Watch a lesson (independent work, grades K-1)

Starting with a read-aloud of The Snowy Day, the teacher introduces the students to a sequencing activity they will be doing independently in which they fill in previously introduced sequencing words and match pictures representing events in the story to the sequencing words. (Watch from 8:09)

Collect resources

Story maps provide one way to help students organize the events from a story.

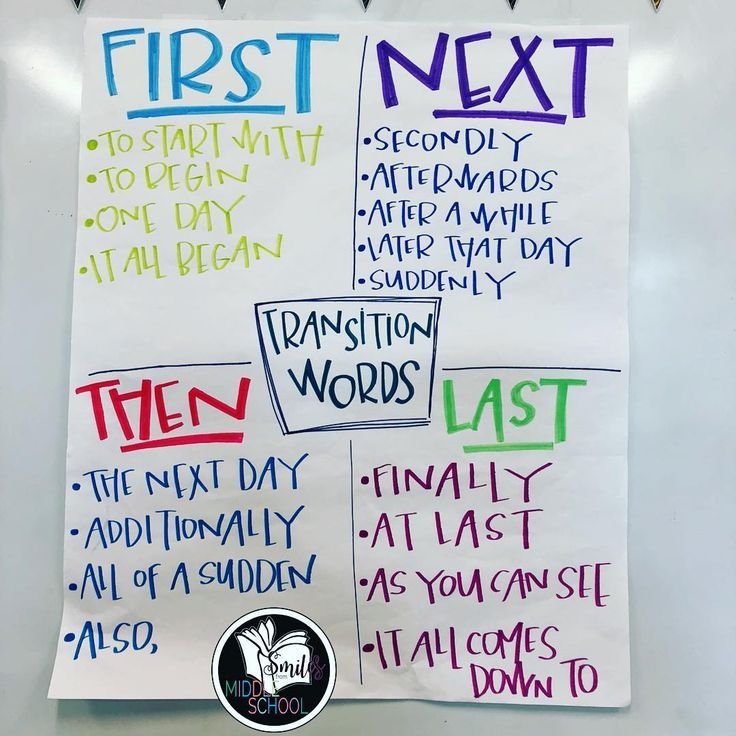

Transition or signal words that indicate a sequence (first, second, last) can help structure a sequencing lesson.

Sequence sticks, story chains, story retelling ropes , and story sequence crafts all help students practice ordering events within a story. See these resources for ideas:

Differentiate instruction

For second language learners, students of varying reading skill, and younger learners

- Scaffolding instruction by providing prompts for each section of the story map you are using. For example, in the “Beginning” box of your map, write in prompts such as: Who is the story about? Where does the story happen?

- Varying the complexity of story maps and sequencing words used. Some students may benefit from the very simple beginning-middle-end format. More complex sequences, such as first-next-then-last, can be used with students who are ready.

- Using wordless books. There are many wordless books that can be used for sequencing with younger students and with English language learners or students with limited English proficiency. For younger students, Pancakes for Breakfast by Tomie dePaola, which humorously details a woman making pancakes from scratch, or the wordless adventures by Mark Newgarden about a small dog named Bow-Wow (e.g., Bow-Wow Bugs a Bug) are good options. Books by Barbara Lehmann and David Weisner are helpful for older or more sophisticated students practicing sequencing.

- Using books in translation for picture sequencing activities. Providing English-learners with a copy of the text in their first language allows them to participate in sequencing and demonstrate their understanding of the concept and the content.

- Modeling sequencing with a smaller group of students using a familiar book with a very clear narrative structure to help students understand each story component.

Extend the learning

Writing

Students can use sequencing words and charts to help them write summaries of texts they have read or heard. They can also use sequencing as a pre-writing technique for planning their own writing or use a sequencing word anchor chart as a writing tool.

Math

Most math curricula include worksheets on ordinal numbers (first, second, third, etc). You can support students’ sequencing ability by encouraging the use of vocabulary words such as “What bead goes first? Then which bead? Which bead is third?” Encouraging students to write out the steps for solving addition and subtraction problems that include regrouping is an excellent way to have them think through the steps in a logical order.

Science

Scientific inquiry also develops sequencing skills. In order to study or observe changes in something, students must follow along and record, in sequential order, what they notice. Students can document their observations by writing or drawing.

Social Studies

Timelines are a great way to teach sequence in social studies. Students may enjoy making a timeline of their own lives, including important milestones such as when they learned to walk or talk or when they first wrote their name or rode a bike. Once students understand the process of charting important milestones on a timeline, topics from the social studies curricula can be used. Try this printable timeline template.

Other ideas for sequencing

- Arts and crafts activities. Quilt-making and other arts and craft activities may reinforce the idea of sequencing and also introduce math concepts (measurement, addition & subtraction and basic computation, etc). Alex Henderson’s Kids Start Quilting with Alex Anderson: 7 Fun & Easy Projects Quilts for Kids by Kids, Tips for Quilting with Children provides easy instructions for adults quilting with children.

- Cooking. Cookbooks for children can reinforce math concepts (measurement, etc) and sequencing while making connections to students’ reading. The Little House Cookbook: Frontier Foods from Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Classic Stories by Barbara Walker presents recipes for foods mentioned in the Little House series by Laura Ingalls Wilder.

- Everyday activities. Create a sequence page for a simple activity around the house or at school. Fold a blank piece of paper into squares. Start with 4 large squares. For older students, create more squares. Ask kids to draw the steps they know in the order in which the steps occur. For example, draw each step it takes to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich or to brush their teeth.

See the research that supports this strategy

Moss, B. (2005). Making a case and a place for effective content area literacy instruction in the elementary grades. Reading Teacher, 59, 46-55.

Children’s books to use with this strategy

One Is a Snail, Ten Is a Crab: A Counting by Feet Book

Quilt of States: Piecing America Together

Show Way

Owen and Mzee: The True Story of a Remarkable Friendship

Rosie’s Walk

Me on the Map

Benny’s Pennies

Great Migrations: Whales

Marianthe’s Story: Painted Words and Spoken Memories

Nabeel’s New Pants

Sitti’s Secrets

The Keeping Quilt

The Penny Pot