It all started with a question. What was their story? Author Linda Barrett Osborne wanted to find out more about her great grandparents who came from Italy in the 1880s and 1890s to the United States — much like the English who settled in Jamestown, Virginia, in the 17th century.

At a local bookstore reading, Osborne asked, “What is the relevance of immigration to children and young people?” Each of us — young and old alike — has our own story. Didn’t all of us (with notable exceptions, of course) come from someplace else? What would make us leave our home country? How would we like to be treated if we landed on another shore?

History, however, has a way of repeating itself. German and Irish immigration followed soon after English colonies were established in the 1600s. And “Wherever the foreign-born population grew in numbers, nativism usually did, too.” (Osborne, p. 10)

The history of immigration in the United States is not altogether pleasant, but not without hope. And hope often comes in the form of education.

A school not far from the bookstore grappled with the same question posed by Osborne. Staff from the Jewish Primary Day School (JPDS), tackled it head-on when a school-wide project was started at the beginning of the new school year. (Because JPDS is in DC, they do something election-related every four years.) Teachers with children from prekindergarten to grade 6 thought about how they could help children think about what was going on in the presidential campaign and to come up with questions to share with adults.

The result was a Voter’s Guide .

The fifth grade teachers took on the topic of immigration. It started with a question: Why should the children care?

After lots of activities to encourage thinking, the students began to ask more questions and started researching to find answers. Their research came not only from reading both print and online material, it also came from the community. The kids visited other schools, invited experts to the school, and more.

What they learned changed their perspective and their language. The teachers observed that negative descriptions of immigrants so often heard in the media fell away, replaced by more positive, more inclusive, more humane terms.

Was this possible only in a religious school? I don’t think so. That JPDS related Judeo-Christian values to the exploration added humanity to the research and helped personalize what the kids explored.

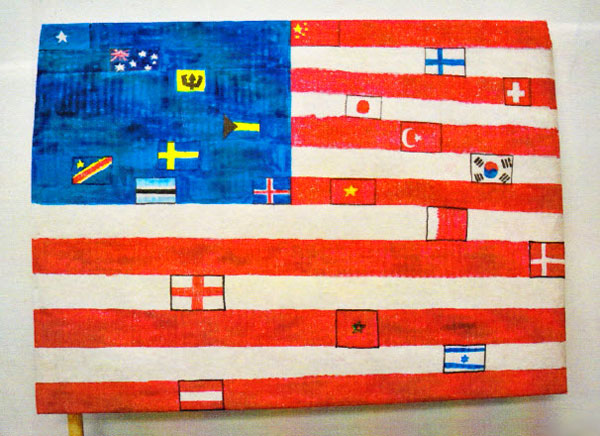

We’re a country of symbols. So, working with art and science staff, the children were asked what they’d like immigrants to see when they come to the United States. (The intra-school collaboration further helps children see connections between subjects and encourages different learning styles.)

One of my favorites is the “Welcome Flag” by Matthew S., Benny H., Ilana K., and Ben L.

Linda Barrett Osborne’s questions have been addressed by a group of students. They found that indeed, learning more about why people immigrate, what they give up, and what they contribute to a community, helps them see the “me” in “them”.

Perhaps most important, it helps prepare these young Americans to grow into the full responsibilities of being U.S. citizens.