Former Kindergarten teacher and world traveler Launa Hall is back with us at Book Life to share part four in her special guest series “Learning to Read Around the World.”

Benvenuto! Welcome to Italy!

Learning to Read in Italy by Launa Hall

Maybe this is the prettiest little school in the world. This was my thought when the school appeared around a corner on the winding mountain road, as I walked from the piazza in Castel d’Aiano to the outskirts of town. The recently renovated school building, sporting cheerful green circles, hovered above a steeply rolling slope.

The kids of this small Italian town in the Apennine Mountains, ranging from preschoolers to high schoolers, played on an adjoining playground and sports field outside their school. The sounds of their play echoed over the hills. The new gym nearby, I later learned, is for days when winter snows are too deep or winds too severe to play outside.

A village school in the Apennines, Italy, in early spring.

I paused to contemplate the scene. Is this the perfect place to be a little kid learning to read? After all, Italian is often cited as possibly the world’s most readable language, owing to its highly regular and predictable spelling. Here, in the country that is the birthplace of the Roman alphabet, I was about to see how literacy is taught under what appears to be ideal conditions.

With this thought in mind, I met Michela, a senior teacher at this school and my very kind and patient guide. She invited me up the stairs; the preschoolers are on the ground floor with easy access to the playground outside, while the middle and high school kids are on the top floor. The primary school is on the middle level, with one classroom for each grade — first through fifth.

Many kids were already outside for their midday break in the crisp weather. One group of fourth graders paused to say hello in English (one of their school subjects) as they donned their coats to join their friends outside. Bright sun streamed through enormous windows in the classrooms and down the hallway. Each classroom had an old-style blackboard on one wall, but also a large digital screen on wheels so it could be moved front and center — or out of the way — as needed. Tidy little bathrooms and a small but well-stocked library served all the primary kids.

But they don’t share everything among the grades — they keep their teachers to themselves. Each grade has two teachers, and those two teachers divide between them the subjects and the hours of the teaching day. One teacher covers Italian, geography, and social studies, and the other covers math, science, PE, and technology. The school’s faculty work together to cover subjects not taught every day, such as music and art.

Even in cities and bigger towns, I learned, Italian primary school teachers work in pairs like this: they divide teaching responsibilities into two spheres. This allows teachers to focus on literacy or numeracy in their university preparatory programs, and allows them to hone more specific teaching skills and plan lessons in their own sphere of teaching.

In addition, teachers tend to stay with a class of children and loop with them through the primary grades. In Castel d’Aiano, for example, the fifth grade literacy teacher was in the middle of selecting the reading curriculum for the incoming first graders; at the end of this school year when she sends her current class of fifth graders upstairs to middle school, she will move down the hall to welcome a new group of first graders in autumn. She and her co-teacher will, ideally, stay with their new class for the next five years, throughout the primary grades. This, I realized, explained a lot about how this school feels — like the kids and teachers truly know each other.

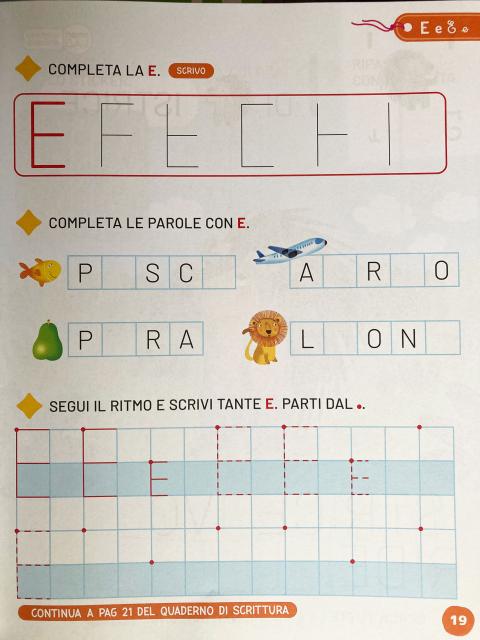

I was intrigued to hear that the fifth grade teacher was choosing her own curriculum. So, there isn’t a national curriculum for teaching reading? I asked. Michela explained that there are standards for each grade level, but teachers can select their preferred curricula to meet those standards. One reading curriculum, for example, starts new readers with all capital letters, while another begins with lowercase, and yet another with a combination of uppercase, lowercase, and cursive all at once.

Page from a curriculum in which children are taught to read in block letters first. Differing methods are in common use in Italy.

This was a point of concern for Elena, a parent of a first grader I spoke with on another day in a different Italian town. Elena’s child is learning capital letters first in her school. This seemed strange to Elena, and she pulled out her own first grade materials from many years ago to check if things had changed. When she was a child herself, she had learned lowercase first and uppercase second, but was taught to write in cursive only. “It worked so well,” Elena said of her own reading education. “I don’t know why methods keep changing.”

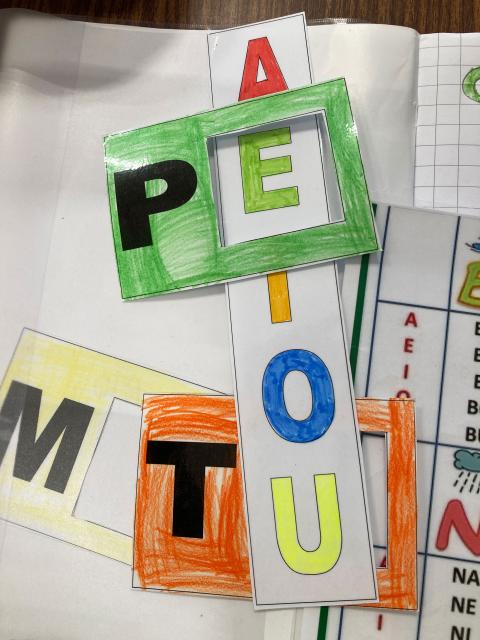

Back in the first grade classroom in Castel d’Aiano, I bent over one of the small wooden tables to take a look at the reading workbooks in use there. While there are many differing curricula and methods, there does seem to be consistency on one point: syllable work. The current first grade curriculum begins with the five vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u), then teaches children to combine those vowels with consonants to create syllables. This method makes good sense for reading Italian; once children can fluently decode consonant-plus-vowel combinations, they are ready to take on almost any Italian word, since this language has a very regular, open-syllable structure. The first grade teacher had created large plastic letter windows to give her young students lots of practice combining consonants with vowels.

Tactile manipulatives to help children build fluency in reading open syllables, the building block of Italian.

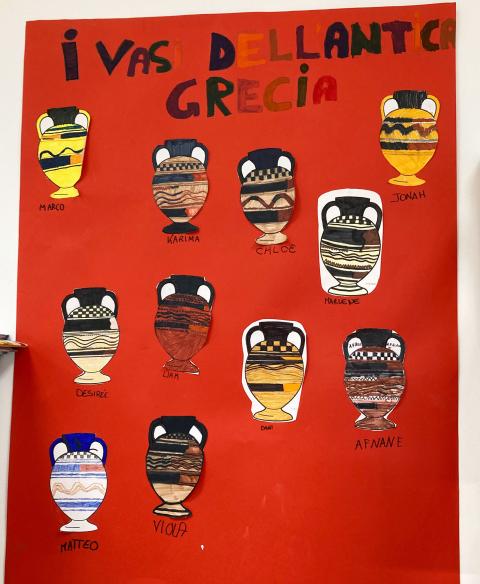

Children’s artwork graced almost every wall space in the Castel d’Aiano school. Some of it was related to books the class had read together, and much of it was connected to field trips they had taken. I learned that field trips are heavily emphasized here — the teachers plan many trips throughout the year, taking advantage of their relative proximity to excellent museums and other cultural sites in nearby cities. One wall, for example, displayed the paper Grecian vases the children had made after seeing them in person in an exhibit in Bologna. I asked if her school was influenced by the philosophy of the Reggio Emilia, a consortium of schools in the region that emphasizes learning through exploration and creativity with lots of access to excellent art materials. She said no, not specifically — her school uses field trips and artwork toward their learning goals because the teachers have found that they help children learn, not because they are following a particular model.

Field trips — and follow-on learning activities inspired by the trips — are emphasized in Castel d’Aiano.

“Your school is wonderful,” I said to Michela, pointing out that the teachers’ close relationships with the children was clear. She agreed, but of course, she said, there are some issues. Specialists to help children with speech and learning difficulties are stretched across a wide caseload at multiple schools; children who recently moved here and who are new to Italian are under pressure to gain grade level reading proficiency very quickly; and there are growing concerns about children’s waning attention spans. Even here, it seems, in this lovely little village school, teachers face many of the same issues that teachers face everywhere.

But then Michela smiled and said that yes, she saw what I meant — her school is wonderful. “Teachers make the school,” she said, and that’s why she loved teaching here, because of her fellow teachers who really care about the town’s children and continue to learn new things for their students.

As I said goodbye and walked back down the road breathing in the fresh mountain air, I considered what I’d seen. I thought it was going to be Italian itself that made this a great place to learn to read. It’s true that a straightforward writing system is a huge plus, although I learned that even with that benefit, teaching reading is a complex topic and methods continue to change. But I was more struck by what can be accomplished when a group of well-trained teachers, given reasonable class sizes, a sensible schedule, and a structure that fosters strong bonds with students, come together to create a school environment. The result is something special.

Takeaways from teaching reading in Italy

- There is so much to know to teach a child to read. Italians acknowledge that teaching young children to read is its own robust field of study. The profession of teaching primary grades is organized into two spheres in Italy: literacy and numeracy. This is true even though Italian has highly regular spelling and is relatively easy to learn to read. Since American schools teach reading in English — a writing system with a much deeper orthography — we might benefit even more from organizing the primary school day around the expertise of two teachers: one teacher focused on literacy and one on numeracy.

- Comprehension is built on background knowledge. When kids know something about the subject matter, their comprehension rates soar. The teachers I visited in Italy know that field trips are a fantastic way to build background knowledge, and they prioritize getting their students out of the building on trips throughout the school year.

- Teachers of reading need ongoing professional development. Even in Italy, where learning to read is arguably simpler than in other writing systems, there isn’t total agreement on what is the best way to teach it, and curricula differ. Teachers must develop their knowledge about teaching reading, honing their skills and continuing to learn about best literacy practices throughout their teaching careers.

- Relationships create success. When educators build strong relationships with students — even over multiple school years — they have a powerful means to fully understand and meet children’s individual learning needs.

Resources

- Launa at Large

- Launa Hall’s Field Trip Notebook

- Literacy Italia Association

- Initial Teaching of Reading and Writing in Italy by Dr. Tiziana Mascia, University of Urbino