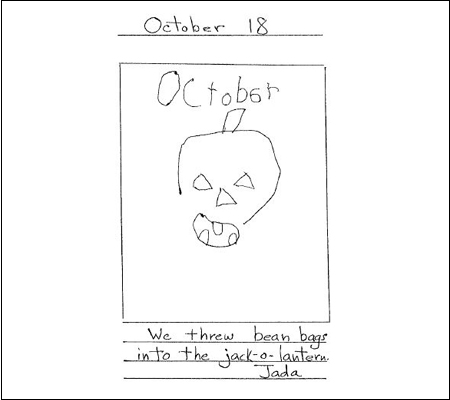

The figure below is a journal entry of a kindergarten student in a class of all Khmer speaking Cambodian Americans who were learning English. He copied the date from a small whiteboard in the Journal Center, drew a picture, and dictated an entry to his teacher who wrote the words for him in the lined spaces at the bottom.

Rationale

Writing in journals can be a powerful strategy for students to respond to literature, gain writing fluency, dialogue in writing with another student or the teacher, or write in the content areas. While journaling is a form of writing in its own right, students can also freely generate ideas for other types of writing as they journal.

Teachers can use literature that takes the form of a journal by reading excerpts and discussing them with students. There are also books that focus on the idea of using diaries, journals, and logs to write about life experiences. Responding to students’ journals and using dialogue journals between the teacher and student can be an effective means of communication and assessment as well (Atwell, 1998).

Strategy

Introduce journal writing through reading aloud an illustrated picture book for younger students, or a chapter book for older students, that uses the journal or diary format. Discuss the book using aesthetic reader response questions and prompts, and model journal writing features: noting the date, using an interesting sentence starter for a journal entry, and mini-lessons on writing conventions.

Journal writing can be done at a set time during a class period or day, or students can write in journals sometime during the day. Monitor the latter through a checklist, noting whether or not students are writing in them. Journals can also be part of writing conferences with individuals or small groups. They can also be used to address writing conventions and questions and needs students may have about spelling, punctuation, word usage, or grammar. Students can choose to share what they have written, or they can share an idea from the journal that they would like to explore further with another type of writing (e.g., poetry, story, or letter). Journals can be used in conferences to discuss these other writing forms.

For example, students could write from the perspective of a personified character, such as an animal or other nonhuman, to personify, research, and learn more about the personified character, and they could write a fictionalized version of a diary. The same could be done with a historical figure or a fantasy creature. Students could put themselves in the place of the character they have learned about, personified, or imagined and write from their point of view.

Students could form pairs and personify, pick, or create characters that would have very different points of view. For example, two 5th grade students learning about the Civil War could work as a team and read about the lives of soldiers from the North and the South. They could discuss similarities and differences and each write a journal from the perspective of one of the soldiers, either a Yankee or a Rebel.

Students could do the same in groups, each writing a journal from the perspective of one person in a mutual context. For example, a 3rd grade class learning about world communities could write a journal about a single issue (e.g., the environment, from the point of view of a leader from one of several countries-the United States, China, India, a member of the European Union, Egypt, etc.). Students in a 6th-grade class learning about the ancient world could do the same from the perspective of an ancient Greek or Roman citizen.

Do a mini-lesson on point of view in writing and make a poster that students can refer to when writing.

Grade-level modifications

K–2nd Grade

Introduce kindergarten or 1st-grade students to journaling by reading aloud a picture book, such as An Island Scrapbook: Dawn to Dusk on a Barrier Island (Wright-Frierson, 1998), or an illustrated book in a journal format for 2nd-grade students, such as Amelia’s Notebook. (Moss, 1995), and lead a discussion using aesthetic reader response questions and prompts: What was your favorite part of the journal? What would you write in a journal?

Record students’ responses on chart paper to model the journaling process. The chart could be titled “Our Class Journal” and the date added. Continue modeling with the class journal and have students take the pen and add to the entries using interactive writing until students are ready to begin their own journals.

Students who are just beginning to write can also go to a Journal Center, which would include multiple copies of a blank frame for drawing and writing a journal entry that could be kept in a file box. The day’s date could be written on a sentence strip or a small whiteboard in the center. Beginning writers can go to the center, copy the date, draw a picture, write, or have someone else take dictation and write for them-perhaps an aide, a classroom volunteer, a more capable peer, or an older student in another grade who spends time assisting in the class. Each student who uses the Journal Center can keep his or her journal entry in a manila file folder labeled with their name. They can also choose to share journal entries during time for sharing with the class.

Recommended children’s books

- Amelia’s Notebook , by Marissa Moss

- An Island Scrapbook: Dawn to Dusk on a Barrier Island , by Virginia Wright-Frierson

- A North American Rainforest Scrapbook , by Virginia Wright-Frierson

3rd Grade–5th Grade

Read Diary of a Worm (Cronin, 2003) aloud. Diary of a Worm is a fictional daily journal of a personified worm, revealing some of the good news and bad news about being a worm. The good news is he never has to take a bath. The bad news is he can never do the hokey pokey. The book models journal writing with humor. Lead a discussion using aesthetic reader response questions and prompts: What do you think of the things the worm wrote about in his diary? What would you write about in your diary?

Record students’ ideas on a cluster chart titled “Our Journal Ideas.” Next, conduct a mini-lesson on sentence starters to write an interesting journal. Ask students if they were struck by any sentence starters in Diary of a Worm that made the journal exciting and fun to read. Make a list on chart paper or a whiteboard. Re-read sections of the book to find more and add to the list. Take suggestions from students for other interesting sentence starters for a journal. Make a poster titled “Journal Sentence Starters” that students may refer to with the list of sentence starters from Diary of a Worm and their own suggestions.

Provide students with their own journals: a bound notebook, lined paper in a three-hole binder, or lined paper stapled together. Students can make and decorate a journal cover. Students can write in journals at a designated time during the day, or anytime during the day, but should write daily. Collect a text set of books that use the diary or journal format and do a book talk to introduce each one-provide a brief summary and read an excerpt aloud. Students may read these independently, or they may choose one for a book club group.

Recommended children’s books

- A Gathering of Days: A New England Girl’s Journal, 1830-1832 , by Joan Bios

- Dog diaries: Secret writings of the WOOF society , by Betsy Byars, Betsy Duffey, and Laurie Myers

- Diary of a Worm , By Doreen Cronin

- My Side of the Mountain , By Jean Craighead George

- The Private Notebook of Katie Roberts, Age 11 , by Amy Hest

- Hey World, Here I Am , by Jean Little

- Turtle summer: A Journal for My Daughter , by Mary Alice Monroe

- Z for Zachariah , by Robert C. O’Brien

- Diary of the Boy King Tut Ankh Amen , by June Reig

- The Bittersweet Time , by Jean Sparks Ducey

- Three Days on a River in a Red Canoe , by Vera B. Williams

Differentiated instruction

English language learners

Journals offer many English language development strategies for ELLs. Journaling taps into each student’s prior experience and knowledge and is therefore context-embedded communication. Students can also write in their primary language. Use visuals through graphic organizers by recording students’ ideas for journal writing and do a mini-lesson on sentence starters using a poster to be displayed in the classroom.

Dialogue journals are also useful with ELLs. The students can write in either a home language or English, or both. More proficient English speakers can respond in English. Then, you or another student can write in the journal to create a written dialogue.

Dialogue journals can also be used at home with family members. Students take a journal home and have a family member write in the journal in English or the home language, or students can read what they have written in the journal, a family member can listen and respond, and the student can note in writing in the journal what the family member said. This increases home–school connections and social interaction, leading to language development for ELLs.

Struggling students

Model journal writing using a graphic organizer. Students can be provided with a one-page blank frame that has a fill-in for the date: Today is …. Take dictation or do a class journal writing interactively (see Interactive Writing) or in small groups. Students can also do an oral journal entry and have another student write what they say and read it together, checking for writing conventions.

Assessment

- Journal

The journal itself becomes a valuable, ongoing record of a student’s development in writing over a semester or school year.

- Checklist

If journal writing is required on a regular schedule (e.g., three days a week or every day), students can record the date of each journal entry on a checklist that can be kept in the front of the journal-so the number and dates of the entries can be seen at a glance. Students could also download a blank calendar for each month and check off the days they made a journal entry.

- Conference

Students can bring journals to teacher conferences if there are ideas they would like to share, or discuss writing options, or if they have questions about writing conventions.

Cox, C. (2012). Literature Based Teaching in the Content Areas. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.