Reading comprehension, simply stated, is the act of understanding and interpreting what we read. What happens in our students’ brains as they read is anything but simple! Skilled reading depends on a wide range of abilities — everything from concrete, masterable skills like decoding to complex, hard-to-pin-down thinking skills like making inferences.

What makes a skilled reader?

Why is it that reading comes more easily to some children than others? What makes a skilled reader? Reading researchers have described skilled reading in different ways (Duke, Pearson, Strachan & Billman, 2009; Sedita, 2006; National Reading Panel, 2000), but there are abilities and behaviors that most skilled readers seem to have in common:

- A clear purpose for reading and an ability to monitor and adjust their reading to serve that purpose

- Word attack skills that allow them to accurately, automatically decode words

- Vocabulary knowledge and oral language skills that help them understand the meaning of words and sentences

- Background knowledge, including content knowledge and literacy knowledge

- Thinking and verbal reasoning skills such as drawing inferences

- Strategies for constructing and revising meaning as they read, such as making predictions and asking questions about the text

- The motivation to read and to apply what they learn

Why is “strategic” reading important?

Comprehension “strategies” are behaviors that researchers have consistently observed in skilled readers. We explicitly teach these behaviors so that all of our students can benefit from them. Strategic readers understand what they read, but their comprehension doesn’t stop there. They also notice and reflect on their own reading. By teaching comprehension strategies, we help our students to be aware of their own thinking — to be metacognitive — as they read.

Draw on prior knowledge

We tap into students’ prior knowledge by asking questions like, “What do you know about jellyfish?” And there’s nothing better than seeing the excitement on the face of a first-grade expert who raises his hand to say, “Some jellyfish are phosphorescent!” Encouraging our students to draw on their own knowledge and experience not only helps them understand what they read; it also builds their curiosity and their motivation to read more.

Draw inferences

If we read aloud a story that starts, “She was so excited to get to school that she practically jumped out of bed,” and ask the class, “What time of day is it in this story?” some of our students will infer that the events of the story are happening in the morning.

We can boost students’ ability to “read between the lines” in this way by intentionally calling attention to inferences they (and we) make throughout the day. Over time, they will come to understand that making inferences helps them understand why events are happening in a certain way, why characters act the way they do, and what might happen next.

Self-monitor

Skilled readers monitor their comprehension during and after reading. By helping our students be aware of when they understand and when they don’t, we empower them to “fix” their own understanding and learn more from their reading.

Form mental images

Skilled readers often form mental images — pictures in their mind — as they read. Readers who picture the story during reading, research shows, understand and remember what they read better than readers who do not.

Summarize and retell

Throughout their school years, our students will be expected to determine what is important in texts and to retell or summarize what they have read. By explicitly teaching them to identify and connect important ideas in a text, we give them the tools to remember and synthesize their reading in both oral and written form. In this blog post, How to Teach Summarizing, researcher Timothy Shanahan talks more about why summarizing and retelling are so important for our students.

How … and how much … to teach

A tried and true way to introduce metacognitive strategies to our students is to narrate the process ourselves using a “think-aloud.” We might say, for example: “I noticed that when I read that part about the storm, I got a picture in my mind of the boat tipping sideways and really big waves splashing over the side.” That’s a think-aloud intended to help students understand what it means to make a mental picture.

In recent years, there has been some debate about the value of teaching comprehension strategies. Willingham & Lovette (2014) have compared using strategies to understand a text to deploying “strategies” to build an IKEA desk. The strategies for building the desk might be something like:

1. Think about the desks you have put together in the past;

2. Find the “main” pieces to work with and start assembling

3. As you work, stop and ask yourself if it looks correct.

As Willingham and Lovette explain:

The vague Ikea instructions aren’t bad advice. You’re better off taking an occasional look at the big picture as opposed to keeping your head down and your little hex wrench turning. Likewise, reading comprehension strategies encourage you to pause as you’re reading, evaluate the big picture, and think about where the text is going. And if the answer is unclear, reading comprehension strategies give students something concrete to try and a way to organize their cognitive resources when they recognize that they do not understand.

The limitation of the “strategies” approach to building a desk, though, is that it really only works if you already know how to build a desk! The same is true of comprehension; readers can’t effectively apply metacognitive strategies unless they already understand much of what they’ve read.

Let’s take, for example, the sentence “The earth is only one of the sun’s many satellites.” One student might have read or heard another book about the solar system and infer that the author is referring to the other planets (or other objects) orbiting the sun. But this “strategic” move depends on having a significant amount of vocabulary and background knowledge already in place.

Bottom line? Spending a limited amount of time teaching comprehension strategies can help our students be metacognitive and independent in their reading, but skilled comprehension ultimately depends on language comprehension.

Why is language comprehension important?

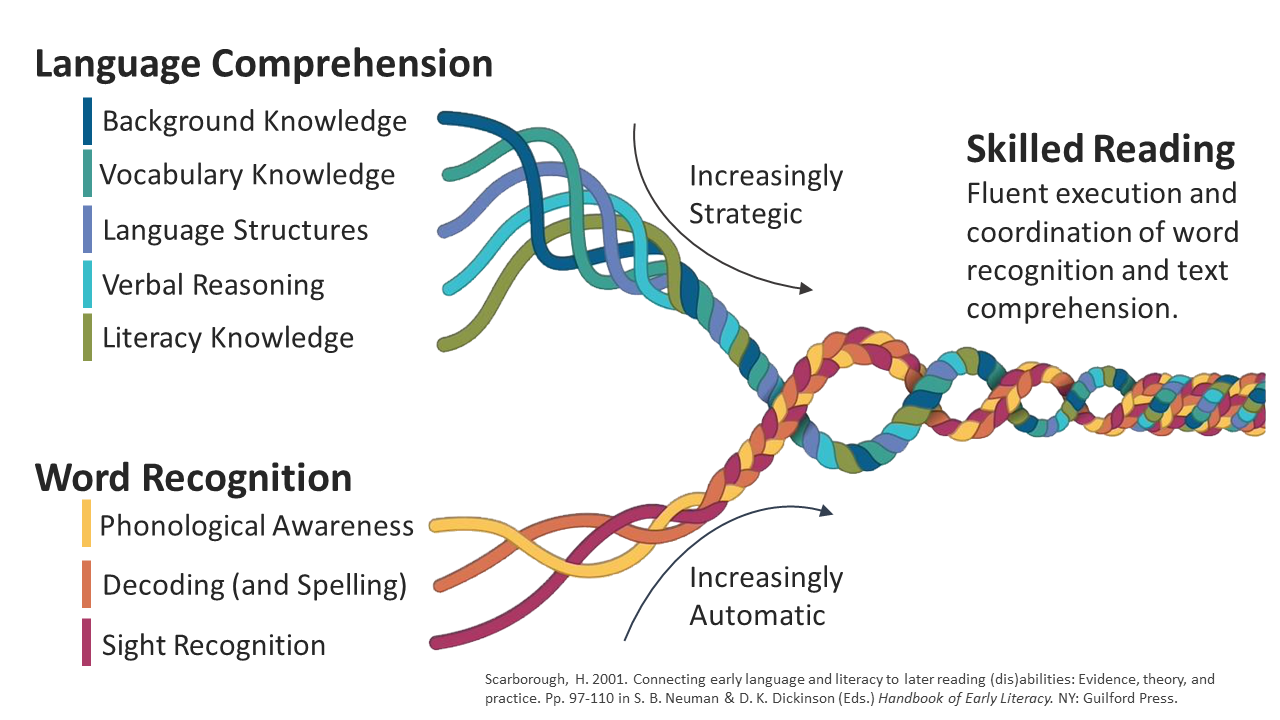

Skilled reading is not possible without language comprehension — the ability to understand spoken language — and word recognition. This is the common-sense concept underlying the Simple View of Reading proposed by Gough & Tunmer (1986). A reader might have strong oral language skills or extensive background knowledge on a topic, for example, but if she can’t read the words on the page, it may affect her ability to understand or to learn from a book on that topic. The converse is true; a student who easily decodes a word but who has never heard the word before or doesn’t know what it means will struggle to comprehend as well. (For a more in-depth explanation of word recognition and recommendations for supporting students in developing strong word recognition skills, see the Phonics module.)

The Scarborough’s Rope model (Scarborough, 2001) goes into more detail than the Simple View of Reading. Scarborough’s Rope looks at language comprehension and word recognition as two strands that twist together into the strong “rope” of skilled reading. The language comprehension and word recognition strands are each woven from smaller strands.

Lessons and activities that build language comprehension are helpful for all students and are particularly important for students who are English-learners or who speak a dialect of English at home that’s different from the texts they encounter at school. Guidance for language comprehension instruction can be found in the “In Practice” section of this module. Additional supports for English-learners can be found at Colorin Colorado.

Background knowledge

The knowledge and language needed to be successful in learning a content topic

Our students understand a text better — and learn more from it — when they have some familiarity with the topic. We can help our students build background knowledge by:

- Encouraging them to make connections to their previous experiences and related knowledge

- Intentionally introducing and discussing new information and connecting it to what students already know

Literacy knowledge

The knowledge and understanding of how books and print materials convey meaning

Our students come to school with different levels of literacy knowledge. Some may not yet know that the print in books carries meaning. Some may flip confidently through a book pointing to the occasional familiar word. Some may already be reading. But our students can still benefit from explicit teaching and rich discussion of:

- Concepts of print: Print awareness plays an important role in our students’ literacy development. It can even be a predictor of future reading achievement. A preschooler earnestly “reading” a book held upside-down is an adorable reminder of why concepts of print matter. See this article to learn more.

- Structures of various genres: Narrative text (stories) and expository or informational text follow predictable patterns and include common elements. No two books are exactly the same, of course, but having a sense of what to expect in a text based on its genre gives our students a framework for comprehension.

| Literary Text | Literary Nonfiction | Informational Text | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

|

|

| Language |

|

|

|

Vocabulary knowledge

The knowledge of words and word meanings

It should go without saying that our students will have a harder time comprehending a text if they don’t know the meaning of individual words in that text. Vocabulary plays a crucial role in listening, speaking, reading, and writing tasks throughout the school day. The good news is, we have many, many opportunities to notice, discuss, and model the use of words throughout the school day as well! (Vocabulary and vocabulary instruction are addressed in greater depth in the Vocabulary module.) The chart below, from the Teaching Reading Sourcebook (CORE), explains the four vocabulary forms:

| Receptive | Productive | |

|---|---|---|

| Oral | Listening Words we understand when others speak or read aloud to us | Speaking Words we use when we talk to others |

| Reading Words we understand when we read them | Writing Words we use when we write |

Language Structures

The knowledge of a language’s grammar

In any language, English included, words and sentences combine in predictable patterns. These patterns make up a language’s grammar — its overall “rules” and conventions — including punctuation, capitalization, word order (syntax), word usage, and verb tense. Because we’ve internalized English grammar, we know that we’re more likely to see a man eating chicken than a man-eating chicken! Dr. Timothy Shanahan addresses the role of grammar in comprehension in more detail in this blog post, Grammar and Comprehension: Scaffolding Student Interpretation of Complex Sentences .

Verbal reasoning

The ability to understand and reason using words

Verbal reasoning is the way we think with — and about — words. Most of the learning our students do in school relies on understanding what we say, understanding what they read, or both. From following directions in kindergarten, to learning to read, to deciphering complex text in the upper elementary grades and beyond, verbal reasoning lets our students follow instructions, understand concepts, and problem-solve around words.

What does verbal reasoning look like in practice? In the sentence, “I ran home and so did he,” verbal reasoning tell us that “he” ran home, too, even though the exact words “he ran home” do not appear in the sentence. And when we read the sentence, “In August, my living room is a sauna,” verbal reasoning lets us know that the author is probably not talking about literally spending summer evenings in a steam-filled cedar box!

What should we keep in mind when matching students to texts?

What makes a text complex?

We know intuitively that Go, Dog. Go! is less complex than Hamlet. But what makes a text complex? The Common Core State Standards (2010) identify three factors that should be considered in evaluating how complex a text is and whether it is appropriate for a particular reader.

Qualitative: Only a knowledgeable human reader can evaluate a text from a qualitative standpoint. When we ask ourselves questions like, “How much background knowledge is needed for my students to make sense of this book?” or “Will this book be accessible to my English-learners?”, we are making qualitative judgments.

Quantitative: The quantitative aspects of a text are things like word frequency and sentence length that we don’t have a practical way to determine for every book in our classroom libraries. Quantitative descriptions of texts (e.g., Lexile level) are typically generated by computer software.

Reader and task: Characteristics of a particular reader (such as level of motivation or background knowledge) and of the task she is being asked to do (such as the format of the response) can help us determine whether a text is appropriate for that reader and for that task.

Supporting documents for the Common Core Standards include lists of high-quality texts for each grade level . For the primary grades, complex texts are taught primarily through read-alouds because our students are not yet automatic in their decoding. By using different texts for different purposes (decodable texts for decoding practice and read-alouds for comprehension work) students who take longer to master foundational skills can still have a chance to develop academic language, vocabulary and background knowledge.

What makes a text “considerate” (or not)

Our students’ comprehension may vary depending not only on their reading and language abilities, but also on how “considerate” a particular text is — how well it accommodates the range of different readers’ needs and abilities. “Considerate texts” (Armbruster & Anderson, 1985) support comprehension through features such as an introduction, a clear sequence of topics, and the use of cohesive words (e.g., however, in summary, for instance). Text cohesion — how clearly sentences are structured and how logically sentences are strung together into paragraphs — can make a text more or less considerate of the reader, too.

The jigsaw strategy

Go inside Cathy Doyle’s second grade classroom in Evanston, Illinois to observe her students use the jigsaw strategy to understand the topic of gardening more deeply and share what they have learned. Joanne Meier, our research director, introduces the strategy and talks about the importance of advanced planning and organization to make this strategy really effective.