About the program

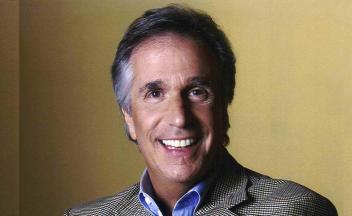

What happens when neuroscience meets Dr. Seuss? Hosted by Henry Winkler, Reading and the Brain explores how brain scientists across the country — in Houston, Chicago, Louisville, Washington, D.C., and Toronto — are working to help struggling readers. Startling new research shows the answer may lie in how a child’s brain is wired from birth.

Exciting new technologies are allowing us to learn on a child’s first day of life whether or not he’ll have a hard time learning to read down the line. And provocative new research from Dr. Stanley Greenspan shows us how emotional interactions between parents and babies are critical to children’s later ability to comprehend what they read.

You’ll also meet poet Nikki Giovanni and illustrator Bryan Collier in a segment about their new book, Rosa, a loving portrait of civil rights icon Rosa Parks.

This 30-minute program is the eighth episode of our award-winning PBS series, Launching Young Readers.

Rewiring the brain

At the University of Texas-Houston, Dr. Papanicolau is using technology to show eight-year-old Peter Oathout his difficulties with reading are rooted in his brain.

Biomapping the brain

In Evanston, Illinois Dr. Nina Kraus thinks that Jenna’s reading problems may be related to the way her brain processes sound. To find out, Dr. Kraus is using some well-known technology in a new way.

Baby’s first reading skills

Drs. Victoria and Dennis Molfese are starting even younger. In Louisville, Kentucky they are studying speech perception in day old babies like Santana Hamond — something that may be a key factor in determining a child’s later reading skills.

The poet and the painter

In Harlem, writer Nikki Giovanni and illustrator Bryan Collier discuss their award-winning book, Rosa, and what it took to write about the influential Rosa Parks.

From emotion to comprehension

Further north in Toronto, six-year-old Arik is reading through his books with lightning speed — but is he understanding it all? Using a technique developed for children with autism like Arik, Drs. Greenspan and Shanker believe that they can help Arik’s comprehension by expanding his emotional connection to the words.

Watch the program

An interview with Henry Winkler

Q: You’ve said that teachers and your own father called you “lazy and stupid” and that you spent a lot of time covering up your difficulties with learning. What were some of the ways you tried to cover up the fact that reading was extremely difficult for you? What signs should parents or teachers look for if they suspect their child or student is “masking” a learning difficulty?

A: I definitely was the class clown. If the teacher read a story out loud, and one of the characters was a hunter shooting ducks out of the air, I became that hunter. I got behind my desk, made the class laugh, and was sent to the principal.

Here it is. A child with a learning challenge is embarrassed by their inability to keep up. They already feel bad. All they need is support, support, a little more support, and then some support. And, ALL of that support must be positive.

Q: Although you endured the pains of growing up with dyslexia, you endured and succeeded in life. What qualities did you have that helped you overcome your learning disability and how can adults help children develop and cultivate those qualities?

A: If there was one word that I would pass on to all children, it would be tenacity. What your school abilities are, and how you perceive your dreams are two very different things. I was not very good at spelling, math, reading, geography, history — I was, however, great at lunch. That being said, my dream of being an actor never wavered.

Being smart does not necessarily correspond to school work. There is intuitive smart, emotional smart, street smart, knowing-how-the-cosmos-works smart. Those incredible pods of intelligence can create a wonderful life without ever getting a passing grade in geometry.

Q: You’ve said your own son is dyslexic as well. How do you hope this show, Reading and the Brain, can help make a difference for kids like your son?

A: I hope that Reading and the Brain allows children of all shapes and sizes, of all ages to know that they have a wondrous gift inside them, and it is their job to figure out what it is, dig it out, and give it to the world.

Q: You understand far more about dyslexia than your own father. As a parent, what special steps do you take to help your own son handle his dyslexia?

A: My wife and I told our 3 children, “As long as you have tried your hardest, whatever your report card says is all right with us.”

I’ve also learned along the way that when my son or daughter listened to music while they did their homework, that it was not necessarily a distraction, but rather the music helped the kids to concentrate. It actually created a barrier between the outside world — whatever else was happening in the apartment — and their focus. When I finally stopped saying “Hey, you cannot do your homework and listen to music at the same time,” and I saw good grades coming home, I realized that this was true.

Q: How does Hank Zipzer fit into this? Do you pull dialogue and situations from your own personal experiences and memories?

A: Hank Zipzer is based on the emotional truth of the stress, the pain, the embarrassment, the humiliation of being dyslexic. AND, what is vital to me, is that the stories are told through humor. The results from the 1000’s of letters that Lin Oliver, my writing partner and I receive from all over the country, is that kids, parents, teachers, and librarians all identify.

Q: What’s ahead for Hank Zipzer?

A: As of this writing, August 1, 2006, number ten is about to hit the stores, number eleven, The Curtain Went Up, My Pants Fell Down, will be out in April 2007, and Lin Oliver and I just started Chapter two of the twelfth novel, Barfing in the Backseat: A Zipzer Family Road Trip.

Recommended resources

From Reading Rockets

Recommended websites

- The Dana Foundation is a philanthropic organization with interests in brain science, immunology, and arts education. Dana offers information to the general public about the progress and promise of brain research.

- Brainy Kids is a site operated by Dana offering children, parents and teachers selected science-related links to games, labs, science fair ideas, educational resources and lesson plans.

Books

- A Good Start in Life: Understanding Your Child’s Brain and Behavior from Birth to Age 6 by Norbert Herschkowitz, M.D. and Elinore Chapman Herschkowitz

- The Scientist in the Crib: What Early Learning Tells Us About the Mind by Alison Gopnik, Andrew N. Meltzoff, and Patricia K. Kuhl

- Magic Trees of the Mind: How to Nurture Your Child’s Intelligence, Creativity, and Healthy Emotions from Birth Through Adolescence by Marian Diamond and Janet Hopson

Awards

- First Place in the Children’s Health category, International Health & Medical Media Awards (the Freddie Awards), 2007

- Silver World Medal at the International Film and Video Competition of New York, 2007

Transcript

Henry Winkler: The human brain holds lots of secrets. like why some kids learn to read easily, while so many struggle. Now brain scientists are looking inside for answers.

Krista: Are you ready to take some pictures of your brain?

Dr. Andrew Papanicolaou: It’s like trying to paint with your toes.

Henry: And they’re showing how good teaching can rewire a child’s brain, turning a struggling reader into a good one.

Anthony: Happy birthday, Thomas!

Henry: “Reading and the Brain” was funded by The United States Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs.

Henry: Hi, I’m Henry Winkler. Learning to read was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done. You know why? Because I’m dyslexic. When I was a kid, people called me lazy, unfocused, dumb. Now to me, reading looked like a magic trick, and I wasn’t in on the secret. That’s why I’m so excited about the stories that you’re about to see. Today, brain scientists are beginning to unlock the mysteries of reading. So let’s take a look at their promising work and meet some of the kids they hope to help.

Kids reading: Captain and Mrs. Keller were overjoyed.

Henry: These kids are barely old enough to tie their shoes, but they’ve already mastered an amazingly complex job: turning lines and squiggles on a page into stories.

Kids reading: …my pencil jumped from my hand.

Henry: Dr. Andrew Papanicolaou is trying to find out how they do it by looking inside their brains. He pioneered the use of magnetoencepholography, or M.E.G., for studying how they read. But he was an accidental pioneer.

Dr. Andrew Papanicolaou: We never looked for dyslexia; it looked for us.

Henry: M.E.G. measures the magnetic field that brain cells create when they communicate with each other. The giant white hat here contains liquid helium — very cold stuff — which helps the sensors detect these tiny fields.

Dr. Papanicolaou: We were using magnetoencepholography to find out what side of the brain is involved in speech.

Henry: While testing one man with epilepsy, Dr. Papanicolaou noticed something very peculiar. When the patient was listening to someone talking, his brain showed primary activation on the left side, like most people. But when he was reading, the activation appeared largely on the right side.

Dr. Papanicolaou: So we thought maybe we had the wires crossed, you know? So we did the test again and again, and then once in a while, it’s good to look at the patient and not only the machines. The person seemed to have difficulty with squinting, and someone asked him, “Can’t you see the words? Is that why you have difficulty reading? Can’t you see them?” He said, “No, I’m dyslexic.”

Henry: Dr. Papanicolaou was hooked. And since then, he’s been trying to understand how our brains work when we read. His findings match those of researchers doing functional M.R.I. studies, like Sally Shaywitz at Yale, and Guinevere Eden at Georgetown. While the entire brain is involved when we read, Dr. Papanicolaou found that a high level of right-side activation is a kind of cerebral signature of dyslexia. And that’s what he saw in Peter Oathout, an eight-year-old who first met Dr. Papanicolaou at a much more trying time.

Mark Oathout: The teacher said that he just broke down and started crying during the test. And she said he was just so frustrated because he knew he could answer the questions and he didn’t want to quit, but he couldn’t read the questions.

Henry: Peter’s parents went online and found Dr. Papanicolaou’s research study.

Dr. Marbel Brones: Come on in!

Peter Oathout: Just wondering, are you gonna put that thing on my head?

Dr. Brones: Yes, we are.

Henry: Peter’s brain showed a pattern of activation like other people with dyslexia tested in the study. Peter was expending more energy on the right side of his brain than good readers typically do.

Dr. Andrew Papanicolaou: It’s like trying to paint with your toes, rather than with your hands. I mean, you are doing something using perfectly normal equipment, but not suitable for the purpose.

Henry: To use another metaphor, while good readers use the interstate highways of their brain, Peter was using country roads to get to the same place. But there’s good news.

Dr. Dennis Molfese: The brain is incredibly plastic, and we know that as you learn new information, the brain physically changes — the neurons themselves, the brain cells themselves — change structurally.

Henry: So how do we go about rewiring a child’s brain?

Dr. George Hynd: Through certain kinds of reading instruction, very carefully controlled, very intensive, these patterns of brain activation can be changed, while at the same time, the children’s ability to read increases.

Henry: Dr. Papanicolaou’s study involved intensive research-based reading instruction.

Dr. Eldo Bergman: Children who are struggling readers and don’t get intervention do not get better.

Henry: Dr. Eldo Bergman is director of the Texas Reading Institute. now both of his sons have dyslexia, and because of that, he’s devoted his life to helping struggling readers like Peter.

Dr. Bergman: Peter came into us as a kindergarten student, frustrated with reading and a phonologically-based reading disorder.

Henry: Peter was tutored every week at the Texas Reading Institute. He worked intensively on his reading skills — connecting sounds to letters, and learning to blend sounds. He practiced the same skills every night with his dad, who was trained by Dr. Bergman and his team. And after a year, the results were really impressive.

Peter: Mr. Duke, the coach, would explode if they were late.

Dr. Bergman: Peter came to us reading in the bottom ten percent. And when he finished his ability to pull words off the page was better than average. And his comprehension had gone from bottom ten percent to the 85th percentile.

Mark: Okay, good; and this one, I think you corrected it. What is that word?

Peter: Ignite.

Henry: Good teaching made Peter a better reader, and changed his brain in the process.

Dr. Papanicolaou: When children receive the appropriate sort of intervention, then their brain profile of activity changes and becomes like the normal.

Henry: And the change goes well beyond the lab.

Mark: I mean, to see your child go from being unhappy and without self-confidence, to being a happy, excited-to-go-to-school kid, it feels like a miracle.

Henry: We’re only beginning to understand how brain imaging might help.

Dr. Papanicolaou: One of the problems, usually with new technologies, is that they tend to be oversold. Many people may be ready to say, “Well now, we are going to use M.E.G., F.M.R.I, to diagnose dyslexia,” I think that’s jumping the gun.

Henry: Dr. Papanicolaou says imaging can complement the kind of assessments done by teachers and school psychologists.

Dr. Papanicolaou: The more you examine an issue from different points of view, you get a more complete picture.

Henry: In Evanston, Illinois, Dr. Nina Kraus is trying to fill in one small part of that picture.

Dr. Nina Kraus: Generally there are many factors that might contribute to why a child is having difficulty reading.

Dr. Hynd: It’s a very big puzzle, a complicated puzzle. Reading’s an extremely dynamic, complicated process, it involves the whole brain. It involves everything from looking at the word and perceiving what’s on the written page, to the whole brain really constructing an understanding of what’s being read. What that means is, that any place along that complicated trajectory or that process, something can go wrong.

Kit Harper: Excellent job, give me five!

Henry: Dr. Kraus is helping to identify or to eliminate one possible cause of a child’s reading struggles — that’s difficulty processing sound. But what does that have to do with reading? Everything!

Girl reading: …with lots of rooms to play in.

Henry: The 26 letters of our alphabet are a code for the sounds that we make when we speak. So if we can’t understand the sounds, the letters won’t mean much. Eight-year-old jenna rogers is here to see if that might be part of her problem.

Krista: Ready to take some pictures of your brain?

Jenna: Mm-hmm.

Krista: All right!

Henry: Dr. Kraus is using an old technology, E.E.G., in a new way. She calls her measurement a biomap. Biomap stands for biological marker of auditory processing.

Dr. Kraus: What the biomap does is it measures very objectively how the brain responds to sound. We’re looking at responses that are coming from the brainstem, so this is the input into the cortex. that one feel okay?

Henry: The responses are involuntary. So even if a kid is having a bad day, or is feeling nervous about the test, the results will not be affected.

Krista: So did you know that your brain makes electricity?

Jenna: No.

Henry: These electrodes will measure how Jenna’s brain responds to the sound “Da,” as it is repeated like so…

Electronic voice: Da-da-da-da-da-da.

Henry: Now at the same time, Jenna will be zoning out with a cartoon. As Jenna’s brain quiets, Dr. Kraus can get a clearer picture of how Jenna’s brainwaves respond.

Dr. Kraus: That’s rather atypical. It really seems as though she’s reflecting — she’s representing sound in perhaps, her own unusual way.

Henry: Jenna’s brain detects sound a little more slowly than most, and that could be part of her problem with reading.

Dr. Kraus: These lines here represent the brain waves from normal kids, and then these come from dyslexic kids. You can just see how the timing is jittered, how the waves are shifted over. The difference here, we’re talking about tenths, fractions of milliseconds.

Henry: Why would such a tiny difference matter? Well, it turns out that the difference between sounds, like those made by the letters “b” and “p” is contained within a tiny span of time. So if your brain doesn’t process fast enough, you can’t distinguish between the two.

Dr. Molfese: If the child cannot hear that difference between the “b” and the “p” sound, and the parents are talking to them, and saying, “bat the ball; pat the cat,” they might be thinking, “oh, bat the ball, bat the cat.” And all cat lovers will tell you, that’s unacceptable.

Kit: How about “say”, where are you gonna put “say”?

Henry: With the new information about Jenna’s auditory processing, Kit Harper, her tutor, is focusing more on helping Jenna learn to discriminate between sounds. She’s essentially training Jenna’s brain to hear more accurately.

Kit: Can you say the sounds while you make it?

Jenna: Ssss, ahhh.

Dr. Kraus: We learn to speak new languages and sing new songs throughout our life, just as you can train your brain to hear sounds differently as you learn to study a musical instrument. Well, if you know which sounds are not being represented well, you can train your brain to hear these sounds in a more accurate fashion.

Jenna: C-a-m-p! Peek-a-boo!

Henry: If there’s one thing that most researchers agree on, it’s that early intervention is the best way to prevent reading problems. Reading experts like to catch kids at three or four, when language problems often emerge. But what if you could start even earlier?

Henry: Santana Hamond’s not quite ready to start reading, he’s only one-day-old. But doctors Dennis and Victoria Molfese believe they can look into his future.

Dr. Molfese: We’re interested in studying speech perception in infants because we think there is a link, even at the very earliest stages shortly after birth — within hours of birth — and later, reading skills.

Henry: That’s because one skill that children must have in order to read is already in place by the time the baby is born. The Molfeses are assessing the ability of a one-day-old baby to discriminate between the sounds for the letter “b” and the letter “p”. we don’t know why, but some babies are born with a lesser ability to hear the difference between similar sounds. Or they hear the difference more slowly. And we know from Jenna that this seemingly small skill is enormously important.

Kit: Perfect!

Henry: Santana’s first stop is a hearing test, which he passes.

Dr. Molfese: The discrimination of the speech sounds is really independent of the child’s ability to hear, rather the problem is their ability to not just hear, but then to discriminate between the different sounds.

Henry: Researchers will test that ability in Santana, with this net. Now it might look intimidating, but Santana hardly notices the soft sensors.

Dr. Molfese: We use these nets to pick up on brain activity that’s being generated by the neurons within the brain. If the brainwaves are different, so we get one brain wave to a “b” sound, a very different brain wave to a “p” sound, then we know the infant can discriminate between the sounds.

Henry: Santana’s brain is picking up on the differences between the two sounds. According to the Molfeses’ work, odds are, that with the right opportunity, he will become a proficient reader.

Dr. Molfese: We can predict with about 80% accuracy, from birth, if a child is going to be a good or a very poor reader by as late as eight years of age.

Henry: The Molfeses have begun developing interventions that parents can use to build their baby’s speech discrimination skills. They don’t have any formal results yet, but their best hunch may sound familiar.

Dr. Victoria Molfese: For generations, people have done nursery rhymes with children, and played word games. And all of that word play, now we find out, is important for developing skills in speech discrimination. Children that may be at risk for reading disabilities who may be not as good at hearing contrast between different speech sounds, need extra experience with those kinds of games.

Henry: This speech sound discrimination screen is not available to the public right now, but the Molfeses hope that will change.

Dr. Molfese: It’d be very simple to screen these children for risk of developing a learning disability, and then start intervening before the child has a chance to develop bad feelings about themselves that’s going to interfere with them developing very proficient reading skills that they really need in our society today.

Henry: All right, let’s take a little break, and remind ourselves what all this hard work is for. Because reading can actually be a pleasure. Sometimes it can actually be an inspiration. we’re gonna head to harlem now, to meet poet Nikki Giovanni, and illustrator Bryan Collier. They’ve put together a new children’s book about the power of one person to change the world.

Nikki Giovanni: I would put books on probably chocolate, because a good book is delicious.

Bryan Collier: It was always a visual thing for me, even when my teacher would talk, i would see words float of her mouth.

Henry: Poet Nikki Giovanni and illustrator Bryan Collier hadn’t met until they got together to produce a book about one day in the life of Rosa Parks.

Nikki: Whatever you’re writing should be true to you. So if it’s funny, you should be laughing. If it’s sad, you should be crying. You just pack everything you have into it and then you let it go and see if it flies.

Henry: So when the invitation came to write a story about her friend, Nikki Giovanni worked to make it fly.

Nikki: I had the pleasure of meeting Mrs. Parks about 24, 25 years ago, on a really rainy day in Philadelphia. And I said, “Mrs. Parks, it’s Nikki Giovanni, I’m a writer.” and she said, “Oh, baby, I love that, Nikki, Rosa.” it just took my breath away. I had no idea she knew who I was. I wanted to show her not as a civil rights icon, per se, but as what she was, which is an ordinary woman, who was going to do, and always did do, extraordinary things.

Bryan: When I first got the Rosa Parks book, I read it about 100 times.

Henry: Bryan Collier is an award-winning children’s book author and illustrator. His signature artwork is a mix of watercolor and collage, but he begins with a sketch.

Bryan: And that sketch will turn into me painting in watercolor, and then the collage sort of finds its way in. that’s me gluing and cutting away and adding to the image. A collage is this wonderful metaphor for life. It’s often about small, insignificant moments. Only, when you put them together, that’s when they sort of create this huge event.

Henry: Soon it all comes together, when the two worlds of words and pictures collide, you sometimes get magic.

Nikki: “I said, give me those seats, the bus driver bellowed. Jimmy’s father muttered more to himself than anyone else, I don’t feel like trouble today; I’m gonna move. Mrs. Parks stood to let him out, looked at James Blake, the bus driver, and then sat back down.”

Henry: You know, a great story is one of the best reasons to learn how to read. Now for a lot of kids, like Jenna and Peter, sounding out the words was their biggest challenge. Now we’ll meet a boy who has no trouble reading individual words, but who struggles to make sense of what he reads.

Henry: Here in Toronto, six-year-old Arik Kimber reads like a champ.

Arik Kimber: “It’s windy again,” he said to Emma.

Rose Kimber: It’s very deceiving that Arik can read so well. He can read the word, but if he doesn’t emotionally understand what that word means, it just creates confusion for him.

Dr. Michael Pressley: It’s important to emphasize that word-level reading and comprehension rely on very different processes because there certainly were those pushing the theory that if you just learned to read the words, you would automatically learn how to comprehend. That was the wrong theory.

Henry: Kids struggle with comprehension for a lot of reasons. Some children use all their energy just sounding out the words. Other kids have a limited vocabulary. Or they may just lack the background knowledge they need to make sense of the story. Arik struggles because of the effects of autism. Now you wouldn’t know it right away, but connecting with the rest of the world has always been difficult for him.

Grant Kimber: He was inside himself. He didn’t really want to interact with other people or other children.

Henry: Dr. Stanley Greenspan says that those emotional interactions are the foundation for understanding what you read.

Dr. Stanley Greenspan: The richer your emotional interactions early in life, the more understanding you have of the world, the easier it is then, to have the words that you’re learning have meaning. For a nine-year-old to comprehend an abstract concept like justice that they might be reading about, they have to have lots of emotional experiences with being treated fairly and unfairly.

Henry: Dr. Greenspan is a renowned child psychiatrist. He spent decades observing babies, including healthy ones, like Milikah. He’s been a leader in the study of the relationship between emotion and intelligence.

Dr. Greenspan: Historically, we’ve always thought, going back to Descartes, that emotions and reason or intelligence were two separate and competing facets of human existence, where the reason controls and regulates the emotion, which is your passions.

Dr. Greenspan: Oh, good; see, protest is good, too!

Dr. Greenspan: But what we’ve discovered in our research — both by studying human babies, but also by looking at human evolution — is that actually, our emotional interactions gives birth to our ability to use symbols, and to think, and eventually to be reflective. it’s a radically new way of thinking about how intelligence forms.

Henry: To tap into Dr. Greenspan’s theory, the Kimbers have been using a technique called floor time. the goal is to increase arik’s ability to engage emotionally, which Dr. Greenspan believes can help lay the foundation for improving his reading comprehension.

Jehan Shehata-Aboubakr: The beauty of floor time is it has emphasized the role of emotion in learning. The child is motivated, the child is interested, and this is your opportunity to work with language.

Arik: My birthday’s august 12th!

Jehan: Oh, you’re all born in the same month, in august!

Arik: All in the same month!

Jehan: All in the same month!

Henry: Floor time is just one aspect of the work Arik is doing to learn how to comprehend. Struggling readers need explicit instruction in how to make sense of what they’re readinG. In Arlington, Virginia, six-year-old Anthony sigall has his own struggles with understanding what he reads. His parents turned to Lindamood-Bell Learning Processes for help. Here they teach Anthony to visualize what he’s reading, a key aspect of comprehension.

Angelica Benson: Well, Einstein said, “If I Can’t picture it, I can’t understand it.” And if we don’t have a way to represent what we’re reading about internally, using imagery, it’s going to be very difficult for us to be able to develop knowledge.

Instructor: When you see the boy’s eyes, what shape do they look like?

Anthony Sigall: Ovals.

Instructor: Ovals? Very good, can you give me a whole sentence?

Angelica: The program starts at a very basic level, where we have a child look at the picture and try to describe it in an appropriate and accurate way.

Instructor: Can you tell me anything else in this picture that i should see?

Anthony: He’s biting.

Instructor: Biting? What’s the chick biting?

Anthony: The boy.

Henry: Anthony’s instructor encourages Anthony to be more and more detailed in his descriptions. His next step will be to describe an image he pictures in his head, based on a word given to him by his instructor.

Instructor: I’m picturing a stop sign in my mind and it looks blue.

Anthony: Thumbs up or thumbs down?

Instructor: I’m picturing a stop sign that looks red!

Henry: Eventually Anthony will work his way up to sentences, paragraphs, and stories. Even at this early stage, his mom is seeing benefits.

Beth Sigall: When he’s looking at pictures or books, or reading with us, he can now look at the picture, understand the words in a way that gives him that gestalt or that whole meaning.

Henry: While this intervention is particularly effective with kids who have autism, it has been shown to help other kids who struggle with comprehension, too.

Angelica: The most important lesson that there is in this, is that we can stimulate the brain, and we can teach an individual how to comprehend and how to process information effectively.

Anthony: Happy birthday, Thomas!

Henry: Back in Toronto, Dr. Stuart Shanker has been tracking Arik’s progress.

Dr. Stuart Shanker: For a kid that’s going through the stages of emotional development, the word apple isn’t just the name of a fruit that’s round, shiny, and red. It’s the name of something that’s juicy, and makes a yummy, crunchy sound when you bite into it. But for a kid who’s not been taken through these stages of emotional development, “apple” is just a label.

Henry: As Arik develops his ability to connect emotionally, and to communicate, Dr. Shanker and his team take a look inside his brain. We now have the technology that we can actually map the child’s emotional development against the child’s brain development. They measure the electrical signals that travel from Arik’s brain to his scalp, as Arik does things that might engage him emotionally, like looking at familiar faces.

Dr. Shanker: And what we can do is process that information and look at how fast he’s able to recognize his mother by looking at certain characteristic signatures in the brain.

Henry: As he develops the ability to make emotional connections, Arik is blossoming.

Arik: All he does is sniff the pictures!

Henry: And he’s begun to find meaning in what he reads.

Rose: He’s finding humor and the expressions on the people’s faces now. It’s not just hurry up, get through the book, read the words, go to bed. Taking that extra time to point at the picture, and point at the faces of the people. And all of the little things going on in the background, that’s part of the book, and that’s what captures him.

Arik: …he scores, at the good old hockey game!

Mr. Kimber: Turn the page.

Henry: I remember the day I found out that my oldest son, Jed, had dyslexia. As all the experts were talking about him, I remember thinking, “Wait a second, they’re talking about me.” Today the best hope for a struggling reader remains that brain surgeon in the classroom — a talented teacher. Researchers are working to give teachers even better tools, so that kids like Peter, Jenna, and Arik, can avoid years of frustration and jump into a good book.

To learn more about “Reading and the Brain,” please visit us on the web, at pbs.org.

“Reading and the Brain” was funded by The United States Department of Education, office of special education programs.

We are PBS.