Students have to be taught how to write. However, it’s not as easy as assigning a prompt and telling students to get to writing. When teachers simply assign (or cause) writing, student achievement suffers (Fisher & Frey, 2007). In fact, there is evidence that student writing achievement has been stagnant for years.

Current expectations outlined in most state standards and the Common Core State Standards suggest that students need to write opinions and arguments with evidence, write informational pieces that include details, and write narratives that are highly descriptive. Writing is something that students should do routinely. As noted in Writing Anchor Standard 10, students should “Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audience” (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010, p. 18).

As part of the literacy block, teachers provide focused instruction on the composing process. This includes attention to genre, structure, mechanics, and voice. Teachers model the composing process for their students and provide students time to write during school. They also engage students in writing conferences and encourage peer reviews of written products (e.g., Nauman, Stirling, & Borthwick, 2011).

However, writing cannot be limited to the literacy block if students are to succeed. Writing to learn, in mathematics, science, social studies, and the arts, is an important consideration for elementary school teachers (Knipper & Duggan, 2006). Given the increased attention and focus on writing as a performance assessment tool, wise teachers frequently check for understanding through student writing, and they do so across the content areas. In this column, we focus on three instructional routines that teachers can use to facilitate student writing across the day.

Power writing: building fluency in composition

Teachers and researchers understand that fluency is an important consideration in reading development (Rasinski, 2102) but sometimes neglect writing fluency. If students do not writing enough, they don’t have anything to edit. Because writing is thinking, if students are not writing fluently, they probably aren’t thinking fluently, at least about the topic of study. That’s not to say that writing fluency makes for a comprehensive curriculum. As with reading, fluency is one aspect that needs to be considered.

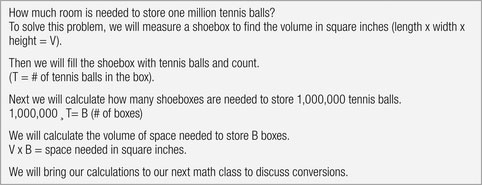

Power writing is a method for building writing fluency through brief, timed writing events (Fearn & Farnan, 2001). The purpose is to get students to put ideas down on paper quickly and accurately. During content area instruction, teachers can integrate a simple daily routine of three one-minute rounds of fluency-building experiences. This will ensure that students have daily practice with writing, which addresses part of the requirements of Writing Anchor Standard 10, the part focused on shorter time frames.

A content area word or phrase is posted on the board, and students are asked to use it somewhere in their writing. Students are reminded to “write as much as you can, as well as you can” (Fearn & Farnan, 2001, p. 196). The timer is set, and writing begins until it rings a minute later. When time is up, students reread what they have written, circling any errors they notice, then count and record the number of words in the margin.

This routine is repeated two more times, until students have three one-minute writing samples in their journals. They then record the highest number of words written (often it is the third sample) on a sheet of graph paper kept in their notebook.

This accomplishes several things for teachers and students. First, and perhaps most obviously, student writing fluency improves with practice. For example, the fourth graders who focused on fluency writing in the Kasper-Ferguson and Moxley (2002) study averaged 10 words per minute, and with graphing their fluency writing activities, they increased to 25 words written per minute, with one student consistently writing 60 words per minute. Interestingly, the authors noted, “Ceiling effects in writing rate did not appear” (p. 249), meaning that the rate was still increasing when the study ended.

Second, students think about the content while they are writing. In fact, students often report that they understand the content a bit better once they have written about it. We have had more than one student tell us, “I didn’t know what I thought until I wrote it down.” This also makes for good assessment of content knowledge, as it provides teachers a glimpse into students’ brains. For example, the students in Mr. Morton’s (all names are pseudonyms) fifth-grade class were focused on the human body and organ systems when they were asked to write about the kidney, lungs, and heart. Mutawali wrote the following: “The kidneys is the part of the body that clean the blood. We got two of them. The shape is like our reading table. They is 5 inches.” It is clear that Mutawali was thinking about this organ as he was writing. Mr. Morton could tell that Mutawali remembered key details.

Third, power writing provides teachers with information about student error patterns. When pressed for speed, all writers will make errors. When students reread their written responses and notice errors, teachers don’t need to worry. When students fail to notice the errors they’ve made, teachers should take note and design additional instruction to address those errors.

For example, in Mutawali’s writing, Mr. Morton noticed the incorrect “to be” verbs and the need for the word clean to be cleans. Taking note of this allows Mr. Morton to plan subsequent instruction, likely as part of the literacy block, to help Mutawali produce academic writing. In doing so, Mr. Morton will help his students master part of Writing Anchor Standard 4, namely, to “Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience” (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010, p. 18).

Writing from sources to inform and explain

Writing from sources is an important aspect of content area learning. Students must use their writing skills to produce pieces that are informative or explanatory. This is especially important in learning science and social studies. As noted in Writing Anchor Standard 7, students should “Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation” (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Offices, 2010, p. 18).

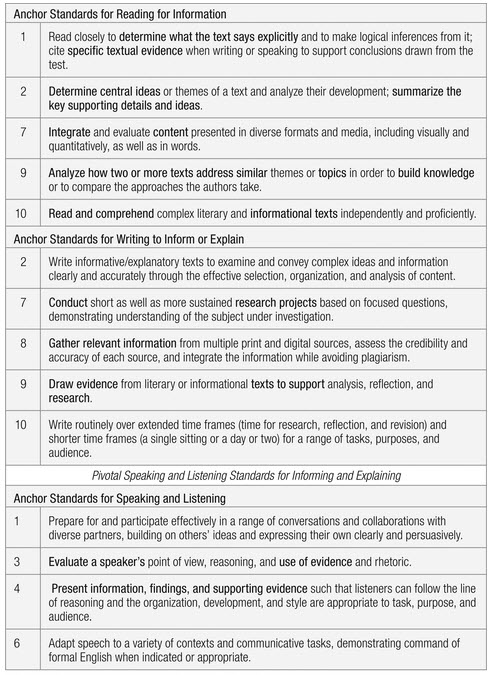

In addition to argument and narrative writing, students should “Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content” (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010, p. 18). It is important to note that this standard focuses on a specific text type that students must learn to produce. The development of students’ understanding of this text type is also influenced by their reading and speaking and listening tasks. Figure 3 includes a list of standards related to this text type across reading, writing, and speaking and listening.

Figure 3. Intersection of Standards for Informing and Explaining

To write from sources, students need to be taught to carefully read texts and collect evidence from those texts. Thus, as part of their content area writing instruction, students should learn annotation skills. In their seminal text, How to Read a Book (1940/1972), Adler and Van Doren suggested that annotation is critical for deep understanding:

Why is marking a book indispensable to reading it? First, it keeps you awake — not merely conscious, but wide awake. Second, reading, if active, is thinking, and thinking tends to express itself in words, spoken or written. The person who says he knows what he thinks but cannot express it usually does not know what he thinks. Third, writing your reactions down helps you remember the thoughts of the author. (p. 49)

They next described the most common annotation marks:

- Underlining for major points.

- Vertical lines in the margin to denote longer statements that are too long to be underlined.

- Star, asterisk, or other doodad in the margin to be used sparingly to emphasize the ten or dozen most important statements. You may want to fold a corner of each page where you make such a mark or place a slip of paper between the pages.

- Numbers in the margin to indicate a sequence of points made by the author in development of an argument.

- Numbers of other pages in the margin to indicate where else in the book the author makes the same points.

- Circling of key words or phrases to serve much the same function as underlining.

- Writing in the margin, or at the top or bottom of the page to record questions (and perhaps answers) which a passage raises in your mind. (Adler & Van Doren, 1940/1972, pp. 49–50)

When students annotate a text, they have sources that they can use to support their claims. For example, as part of their investigation about the Code of Hammurabi, sixth-grade students in George Martin’s social studies class studied the list of 282 written laws. For his students to understand the ramifications of these laws, Mr. Martin used text-dependent questions to guide his students’ annotations. He posed questions and asked for rulings:

- What should happen to a farmer whose dam floods another farmer’s field?

- What if a thief steals possessions being kept in the house of another person?

- What if a father wants to kick his son out of the house?

Students worked with sections of the code to arrive at decisions, citing specific laws. In each of these cases, several laws were involved, and students needed to cite them in their work. “The annotations were essential for this task, because they had to cite the correct laws to build their case for a legal decision. Just like judges of the time, they had to apply formal reasoning to support their claims,” he said. “It’s good for them to see that even though the laws have changed, the work of logic and reasoning governs legal decisions.”

Conclusion

If students are to meet the writing demands stated in the core standards, they need regular opportunities across the learning day to engage in a range of writing tasks. These should reflect a variety of purposes and audiences and should be designed to build knowledge. It isn’t fair to expect that students can get by with an occasional extended writing task and little in the way of instruction and practice. Effective writing teachers know that building stamina, discussion, and knowledge are integral for developing stronger writers.

Biographies

The department editors welcome reader comments. Douglas Fisher is a professor at San Diego State University, California, USA; [email protected]

Nancy Frey is a professor at San Diego State University; [email protected]