Who can understand all the jargon that’s being tossed around in education these days? Why is there a word for everything, and why do they have to be so confusing? Consider all the similar terms that have to do with the sounds of spoken words phonics, phonetic spelling, phoneme awareness, phonological awareness, and phonology. All of the words share the same “phon” root, so they are easy to confuse, but they are definitely different, and each, in its way, is very important in reading education.

Phonics

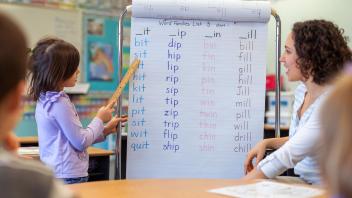

Thanks to the popular “Hooked on Phonics” television commercials everybody has heard of phonics, but not everybody knows what it is. Phonics is a method of teaching that emphasizes letter-sound relationships. Children are taught, for example, that the letter n represents the sound /n/, and that it is the first letter in words such as nose, nice and new.

In addition, and this is something that most people don’t think about when they think of phonics, children are explicitly taught the English spelling-sound “rules.” Children are taught things like “when two vowels go walkin’ the first does the talkin’ ” and “when a word ends in a silent-e, the first vowel sound is long.” Since no letter in English, except for the letter V consistently corresponds to a single sound, these rules are quite complex. Nose, nice, and new all start with the letter N, but gnu, knife, and pneumonia certainly do not. There are spelling and pronunciation rules, and then there are exceptions to the rules, and teachers who use the phonics approach try to formally and explicitly teach both.

For the purpose of discussion here, there are two important things to remember about phonics. First and foremost, phonics is an instructional strategy a method of teaching children to read. Second, phonics has to do with teaching the relationships between the sounds in speech and the letters of the alphabet (both written and spoken). Typically, when somebody is talking about teaching children the “spelling-sound” relationships (or to use some of that psycho-babble ed-speak, the “grapho-phonemic” relationships), they are talking about teaching some form of phonics.

Phonetic spelling or reading

This is a concept which is related to phonics, but unlike phonics, which is a method of teaching reading, phonetic spelling or phonetic reading is a behavior that young readers exhibit when they are trying to write or read. When children spell words the way they sound, they are said to be phonetically spelling for example, the word lion could be phonetically spelled L-Y-N, or the word move could be phonetically spelled M-U-V. Likewise, a child can phonetically read words child phonetically reading the word two may say “twah”, or the child may phonetically read the word laugh in such a way that it sounds like lag or log.

Phonology

Unlike phonics or phonetic reading and writing, phonology has nothing to do with the letters in our alphabet or the letter names (spoken or written. Phonology has to do with the ability to distinguish and categorize sounds in speech. Some words in English (in all languages actually) sound very similar, and are easily confused if you are not very sensitive to the distinctions. For some children with phonology deficits, pairs of words like mauve and moth or rate and late sound identical. They can not hear the difference between certain similar phonemes (speech sounds), and as a consequence, they can not hear the difference between certain words.

Phonological awareness

Like phonology, phonological awareness has nothing to do with the letters in our alphabet it has to do with the sounds in spoken words. And while phonology refers to the ability to hear the difference between sounds in spoken words, phonological awareness refers to the child’s understanding that spoken words are made up of sounds.

This fact is obvious to adults, but children do not usually realize that, within a word, there may be other words (in the case of compound words), or that words are made up of syllables and that syllables are made up of phonemes. Children without phonological awareness do not understand what it means for words to rhyme, they do not appreciate alliteration (words that start with the same sound), and they do not understand that some words are longer than other words (the spoken form, that is, not necessarily the written form the word area in its spoken form is longer than the word though, but in its written form, area is the shorter word).

Phoneme awareness

The phoneme is the basic building block for spoken words. In English, for example, there are an infinite number of possible words, but there are only about 45 phonemes. To make new words, we just delete or rearrange the phonemes mat becomes man when the phoneme /t/ is replaced with the phoneme /n/, and deleting the phoneme /m/ from man leaves you with the word an.

While phonological awareness is a general term describing a child’s awareness that spoken words are made up of sounds, phoneme awareness is a specific term that falls under the umbrella of phonological awareness. Phoneme awareness refers to the specific understanding that spoken words are made up of individual phonemes not just sounds in general (which would include syllables, onsets, rimes, etc.). Children with phoneme awareness know that the spoken word bend contains four phonemes, and that the words pill and map both contain the phoneme /p/; they know that phonemes can be rearranged and substituted to make different words.

Phonological awareness is a step in the right direction, but phoneme awareness is what is necessary for the child to understand that the letters in written words represent the phonemes in spoken words (what we call the “alphabetic principle”). We spend a lot of time teaching children that the letter M stands for the sound /m/, but we rarely make sure that children understand that words like milk, ham and family all contain the phoneme /m/, or that the difference between man and an is the deletion of the phoneme /m/.

Phoneme awareness can be demonstrated in a variety of ways. The easiest phoneme awareness task is called blending an adult pronounces a word with a pause between each phoneme (e.g. /b/ /a/ /l/), and the child blends the phonemes together to make the word (“ball”). A more challenging assessment for children is the reverse, called phoneme segmentation the adult says the whole word, and the child says the word with pauses between the phonemes (adult says “ball,” child says /b/ /a/ /l/). Even more challenging is phoneme manipulation the adult tells the child to say a word without a particular phoneme (say “boat” without the /t/), or the adult tells the child to add a phoneme to a word to make a new word (What word would you have if you added the phoneme /o/ to the beginning of “pen?”). If the child can reliably do any of these tasks, the child has demonstrated true phoneme awareness, but a relevant point to make here is that the child doesn’t need to do much more than these tasks to demonstrate phoneme awareness.

It is possible, in fact it is easy, to create phoneme awareness tasks that are exceptionally tricky, but these should be avoided rather than exploited. English contains many confusing phonemes there are diphthongs and glides that can confuse anybody, even mature, experienced readers (How many phonemes do you hear in pay?), and there are odd phonemes that are not universally defined (How many phonemes are in the word ring or fur?), and there are clusters of phonemes that are harder to segment than other phonemes (a cluster is a group of consonants that are perceived as a unit, sometimes until the child begins spelling for example, the /pr/ in pray, the /gl/ in glow, and the /sk/ in school). It is important for the teacher to remember that the child doesn’t need to be an Olympic champion at phoneme manipulation the child just needs to demonstrate knowledge of the fact that spoken words are made up of phonemes. It is also important that the teacher understands that phoneme awareness is not a magic bullet; it is important, and it is necessary for reading success, but it is only one skill of many that support literacy.

Summary

So to recap, phonics is an instructional approach that emphasizes the letter-sound relationships (which letters represent which sounds). Phonetic reading and writing is a behavior the child exhibits that involves “sounding out” words the way they are written or writing words the way they sound (again, relating to the way letters represent speech sounds). Phonology has to do with the ability to hear the difference between different speech sounds (and has nothing to do with letters of the alphabet). Phonological awareness is a term used to describe the child’s generic understanding that spoken words are made up of sounds. Phoneme awareness specifically refers to a child’s knowledge that the basic building blocks of spoken words are the phonemes.