Traditionally, wordless picture books have been defined by what they do not contain: words. They have also been defined by an assumed readership of young readers who can’t yet read words. This potential bias toward the essential nature of the wordless picture book — which I also call a visually rendered narrative — needs to be rethought in order to consider the potential of this type of book in today’s classrooms. In this column, I would like to challenge both of these traditional ways of looking at wordless picture books and offer a few approaches for integrating wordless picture books into a wider range of classrooms: preschool through middle school.

Literary considerations

To begin, wordless picture books often do contain some words. For example, most wordless picture books contain a title, the author-illustrator’s name, and other peritextual elements like copyright information, author blurbs, and book jacket teasers usually created by the publisher. The textual elements included with these picture books serve to identify the work, designate the topic or focus of the book, and allow readers and librarians to shelve and retrieve the books. In addition, other words are often contained in the illustrations as signs, labels, or parts of the décor, for example; these are defined as intra-iconic text (Beckett, 2014).

In their classic taxonomy, Richey and Puckett (1992) divided wordless picture books into two main types, wordless and almost-wordless picture books, and delineated several sub-categories for each type. They asserted that many wordless picture books contain dialogue, labels, onomatopoeia, text used as a framing device at the beginning and end of the book, symbols, and of course, titles. So, we have to admit that wordless picture books aren’t entirely wordless!

Wordless picture books may be better defined by what they do contain — visually rendered narratives — rather than what they do not contain. In some wordless picture books, the visual narrative is rendered through a sequence of images that contains features typically associated with graphic novels, such as gutters and panels (Low, 2012). Flotsam (Wiesner, 2006) and The Snowman (Briggs, 2002) are two examples of this type of wordless picture book. Other visual narratives are rendered through full-page illustrations. For example, the wordless picture book Chalk (Thomson, 2010) features some of the most detailed, full-bleed sequence of illustrations found in any picture book. The colorful illustrations of the playground setting and the dinosaur that comes to life in the story are simply breathtaking. In this type of picture book, the turning of the page, rather than individual panels, orders and reveals the narrative sequence of images.

Second, all readers can enjoy wordless picture books and should be exposed to them whether or not they can read words proficiently. Being able to make sense of the world begins with making sense of visual information. It goes without saying that young children can read pictures long before they can read words. However, making sense of some of the more complex wordless picture books available today requires being able to understand the conventions of these books, including the sequential rendering of visual information, the drama of the turning page, and ways to navigate panels, gutters, and other design features. The sparse written text that may be included is there to support the visual images, anchor the narrative sequence, and call attention to various aspects of the visual narrative. In wordless picture books, the written text is subservient to the visually rendered narrative. As wordless picture books grow more complex, older readers will find challenges and enjoyment in these texts, which are too often relegated to younger readers.

Pedagogical possibilities

Knudsen-Lindauer (1988) suggested that wordless picture books offer numerous pedagogical benefits for emerging readers, including the development of pre-reading skills, sequential thinking, a sense of story, visual discrimination, and inferential thinking. In addition, Arizpe (2014) outlined the demands that wordless picture books place on readers. In order to make meaning in transaction with these visual narratives, Arizpe suggested five things that readers of wordless picture books must learn to do:

- Give voice to the visual narrative by participating in the story sequence

- Interpret characters’ thoughts, feelings, and emotions without textual support for confirming these ideas

- Tolerate ambiguity and accept that not everything may be answered or understood

- Recognize that there are a range of reading paths to explore through the visual narrative

- Elaborate on hypotheses about what is happening in the narrative sequence

Providing time for readers to immerse themselves in a variety of wordless picture books allows them to enjoy the elaborate illustrations, explore the narrative possibilities these books offer, become comfortable with the absence of written text, and develop understandings of how these books work. Wordless picture books can be used to support readers’ understandings of narrative conventions as they progress toward more sophisticated graphic novels and multimodal texts.

In a recent study, I worked with a high school teacher using Flotsam (Wiesner, 2006) and The Arrival (Tan, 2006) to introduce her readers to the conventions and designs of visual narratives in wordless picture books that are also found in graphic novels. The wordless picture books used in her classroom offered her older readers a relatively risk-free opportunity to share and discuss the visual and narrative conventions that would support their reading of other multimodal texts.

In addition to understanding the visual and narrative conventions of wordless picture books, readers need to be able to interpret what is happening in individual images and illustrations. Facial expressions, gestures, settings, events, actions, and motives all have to be inferred from the sequence of images, since no text is available to anchor the meaning potential of the visual narrative. By discussing a variety of narrative and visual features, we bring forth readers’ implicit understandings of visual images and narrative sequences and make themexplicit so we can examine how they serve the narrative and influence interpretations. As reading teachers, we need to call students’ attention to how these books work in addition to what they might mean.

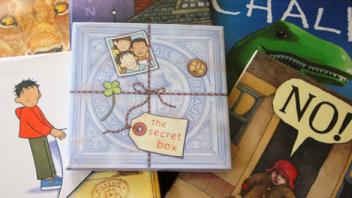

Wordless picture books by Barbara Lehman — for example, The Red Book (2004), Rainstorm (2007), and The Secret Box (2011) — are wonderful visual narratives that keep readers exploring the details of the illustrations over the course of numerous readings. Recent award-winning wordless picture books like The Lion and the Mouse (Pinkney, 2009), and Flora and the Flamingo (Idle, 2013) offer the reader opportunities to explore beautifully illustrated picture books and focus children’s attention on the rendering of the visual narrative.

Wordless picture books are not simply for beginning readers, however. Unspoken: A Story From the Underground Railroad (Cole, 2012),The Middle Passage: White Ships/Black Cargo (Feelings, 1995), and Mirror (Baker, 2010) are sophisticated visual narratives that evoke discussions concerning the types of social issues usually reserved for older readers. As picture books cross over into young adult themes and topics, they become even more important for sharing and discussing with older readers.

Conclusion

From classic wordless picture books like Anno’s Italy (Anno, 1978) and The Snowman (Briggs, 2002) to more recent publications like Wave (Lee, 2008), Journey (Becker, 2013), A Ball for Daisy (Raschka, 2011), and Sidewalk Circus (Fleischman, 2007), the quality of the wordless picture book continues to improve and evolve. The open-endedness and rich visual experiences that are offered in these texts require readers to slow down and pay close attention to the details of the illustrations and the rendering of the visual narrative. As readers are invited to shift from the temporal logic of the written text to the spatial logic of the visual image, we need to find ways to support their meaning-making processes with visually rendered narratives in addition to written language (Kress, 2010).

Imagination is an important part of the process of reading visual narratives. Readers are being asked to actively participate in the construction of the narrative and cannot rely simply on the literal decoding of written text. The open-endedness or ambiguity that is inherent in wordless picture books allows readers to construct diverse interpretations and return again and again to reconsider their initial impressions. Teaching readers to dwell in complex illustrations and to wander through the sequence of images in wordless picture books, exploring the possibilities they offer, is an important part of becoming visually literate (Serafini, 2010, 2012).

In today’s world, being able to make sense of visual images is an essential skill both in and out of school. Too often, being literate focuses on reading written text and not in making sense of the world across modalities, in part because of the logocentric or text-focused nature of schools and society (Bosch, 2014). Teachers need to develop their own capacities for talking about visual images and narratives in order to support the development of these capacities in their readers (Serafini, 2014). Wordless picture books may be the best platform for introducing many narrative conventions, reading processes, and visual strategies to readers of all ages.

Frank Serafini. (2014). Exploring Wordless Picture Books. The Reading Teacher, 68(1), 24–26 doi: 10.1002/trtr.1294