Rationale

The first people were the pirates. The pirates went all around to all the worlds and got all the treasure. Next came the cave men. The cave men lived in the caves at Disneyland. But there weren’t any castles or Popsicle stands yet. But that was all right because the cavemen didn’t like fun. They liked dark and carried big things on their shoulders. Then came the Indians and the Pilgrims. They came at the same time. Then came us.

— World History by Elizabeth, age 5

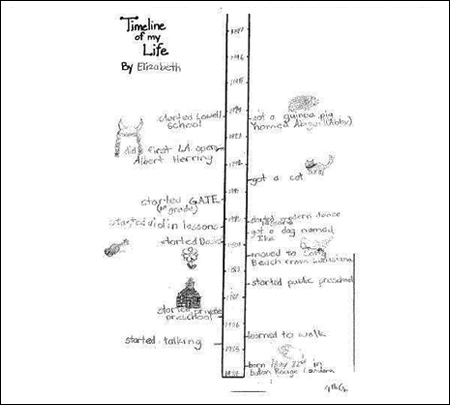

Timelines are graphic representations of the chronology of events in time. While they are often used as a way to display information in visual form in textbooks as an alternative to written narrative, students can also become more actively engaged in learning the sequence of events in history by constructing timelines themselves.

The strategy of timelines can be used with students in Grades K through 8. Research shows that even young children have an understanding of temporal order of events in history and have the ability to think about and try to explain continuity and change over time (Barton, 1997, 2002, 2008; Barton & Levstik, 1996; Downey & Levstik, 2008; Harnett, 1993; Levstik, 1991).

For example, see the explanation of world history that Elizabeth dictated to her kindergarten teacher around Thanksgiving when the class was learning about the Pilgrims. She was clearly thinking about where the Pilgrims fit in the sequence of people in world history. Most upper elementary and middle school students can identify historical developments, especially related to national history, even though they may lack a detailed understanding of those developments (Barton & Levstik, 1998; Lee, 2004; Yeager & Terzian, 2007). A study by Barton and Levstik (1996) with children from kindergarten through Grade 6 using the method of placing pictures and photographs from 1772 to 1993 in sequence showed that kindergarten and 1st grade students are able to demonstrate understanding of differences in historical time. Dates were more useful for older students in Grades 3 and 4, and this ability increased in Grades 5 and 6 as students could match dates with specific pictures.

It’s advisable to keep timelines fairly simple, to cocreate them with students, and to consider alternative chronological representations given the content taught, such as vertical or horizontal timelines, timelines at an angle, timelines that replicate a path taken by people or travelers, or circles (Alleman & Brophy, 2003; Lynn, 1993; Masterman & Rogers, 2002). Timelines as a teaching strategy can help students construct an understanding of historical events over time, even the youngest students. Literature can be used to show, model, and help students develop concepts about time, continuity, and change in social studies as a basis for creating timelines (Hoodless, 2002). Haas (2000) explained how to do this with the book A Street Through Time (Steele, 2004), using timelines and other powerful instructional strategies for social studies.

Strategy

Students can begin with timelines of their own lives. Literature about a child’s birthday can begin a study of timelines with younger students. Many books of children’s and young adult literature for older students, particularly nonfiction history, show timelines. Read and discuss a book with students, leading into the activity of constructing a timeline with events from each of their own lives using a reader response prompt such as “Think about the important events in your life over the years, and you can each make a timeline.”

Each student can begin with their date of birth and then make a list of the subsequent years of their lives, with at least one important event for each year. These lists should be developmentally appropriate for each grade but can become increasingly complex through the grades. Information on what was happening in the world around them can be added as well. Teachers can co-construct the guidelines for creating a timeline with students, depending on their grade and area of study in the social studies (e.g., the family in kindergarten, the community in Grade 3, U.S. history in Grade 5, world history in Grade 6, etc.). These parallel timelines afford students a view of the world during their own lifetime, situating themselves in the context of the historical events of the time.

There are several types of timelines a teacher can choose, depending on the grade, area of study in social studies, and needs of students:

- Horizontal: from left to right

- Vertical: from bottom to top

- Illustrated: pictures added

- Table top timelines: add objects, artifacts, photographs in frames, etc. to a timeline on a table or counter in a classroom

- Circles: this could be a clock or represent a journey that ended where it began

- Computer generated: use Word, Excel, or PowerPoint, adding information to create a personal or historical timeline

- Meandering: a timeline could represent a journey or migration that did not follow a linear path

- Map: put a timeline directly on a map to show both distance, place, and time on a Journey

- Parallel timelines: put a student’s life on the left and world events on the right

- Living timelines: construct a large timeline that uses the walls or floor of the room using lengths of butcher paper; students can learn about and dress to represent historical events and then tell other member of the class, or an audience of other classes, about the period

Technology

Visit the ReadWriteThink website to try the interactive timeline tool .

Grade-level modifications

K–2nd Grade

Read aloud On the Day You Were Born, by Debra Frasier (2005). Use reader response questions and prompts to discuss the book and connect the concept of birth date to each student’s own life: “What do you know about what happened on the day you were born?” Use the following template for students to record dates and events. They can take it home and do it with the help of family members and also add information in class on their own.

The calendar and months and dates of the year are often taught as social studies content in kindergarten. Kindergarten students could use the first line of the template provided, either writing their birth date themselves or telling it to someone for dictation. Each student could illustrate the sentence. Then, make a list of the months of the year, with each student’s birth date written next to the month of their birth, in order by days. After making a wall timeline with the months of the year, each student’s birth date could be added in the correct month. Students in Grades 1 and 2 could create a vertical timeline of their life, using the template provided, with the correct number of years for the grade, typically six years for Grade 1 and seven years for Grade 2.

Recommended children’s books

- Tell Me Again About the Night I Was Born By Jamie LeeCurtis

- On the Day You Were Born By Debra Frasier

- Because of You By B.G. Hennesy

- On the Night You were Born By Nancy Tillman

3rd Grade–5th Grade

Timelines can be created to match appropriate social studies content in Grade 3 (the community), Grade 4 (the state), and Grade 5 (U.S. history). An excellent book to read aloud and have available for students to read in the classroom is How Children Lived (Rice & Rice, 2001). The book introduces the concepts of time and distance and describes 16 children living in different eras of the past, from ancient Egypt in 1200 B.C. up to the 1920s in the United States. It begins with a double page spread showing each child standing where they lived on a world map. Then the life of each child is described in chronological order, with a timeline of the period in which they lived. Discuss the book using reader response questions and prompts such as “What would a timeline of your life look like? How could you also describe the world you live in?” Students can construct a timeline of their own lives like the one Elizabeth made, shown in the figure below.

In all three grades, the study of a period of history can begin with the students’ own community: for example, 100 Years of Our Town. Contact the local historical society for resources. Students in Grade 4 can move on to constructing timelines for state history, and students in Grade 5 can construct one for U.S. history. They can also create parallel timelines by continuing to add to their own personal timeline, as well as adding current events in the world. If they use the vertical format, personal events could be on one side, world events on the other. If they use a horizontal format, the line could run through the middle of a paper, with personal events below and world events above the line.

There are other books with timelines related to American history that could be collected for a text set in the classroom.

Recommended children’s books

- The World Made New: Why the Age of Exploration Happened and How It Changed the World By Marc Aronson

- World War II for Kids: A History with 21 Activities By Richard Panchyk

- How Children Lived By Chris Rice

- Timelines of Native American History By Carl Waldman

Differentiated instruction

English language learners

The context-embedded instruction that is so important for English learners to succeed can be achieved with personal timelines. Students draw on their own life experiences and that of their families as they construct this type of timeline. The timeline itself provides visual support, which is also important in the instruction of students learning English; teachers can use illustrations to clarify timeline content and students can illustrate their own timelines. Students can work in pairs, providing support through cooperative learning as well. Another ELD strategy is to use props, realia, and artifacts, which could be included in a table top timeline.

Struggling students

Construct a timeline frame for struggling students and use templates for gathering information that will be placed on a personal timeline. Model a template on a piece of chart paper using one student as an example, and then each student could complete their own template: “In I” completing one for each year of the timeline. The year and event could be transferred to a timeline with intervals for each year.

Assessment

Authentic assessment of timelines could include a guideline for the elements expected in each timeline, which could also serve as a self-editing checklist for students as they produce the timeline. Elements on the timeline would vary depending on the age, developmental level, varying needs and abilities of the students, and the area of social studies for which the timeline was constructed.