Researchers have made considerable progress in understanding all types of reading disabilities (Fletcher et al., 2007). For purposes of research, “reading impaired” children may be all those who score below the 30th percentile in basic reading skill. Among all of those poor readers, about 70-80 percent have trouble with accurate and fluent word recognition that originates with weaknesses in phonological processing, often in combination with fluency and comprehension problems. These students have obvious trouble learning sound-symbol correspondence, sounding out words, and spelling. The term dyslexic is most often applied to this group.

Another 10-15 percent of poor readers appear to be accurate but too slow in word recognition and text reading. They have specific weaknesses with speed of word recognition and automatic recall of word spellings, although they do relatively well on tests of phoneme awareness and other phonological skills. They have trouble developing automatic recognition of words by sight and tend to spell phonetically but not accurately. This subgroup is thought to have relative strengths in phonological processing, but the nature of their relative weakness is still debated by reading scientists (Fletcher et al, 2007; Katzir et al., 2006; Wolf & Bowers, 1999). Some argue that the problem is primarily one of timing or processing speed, and others propose that there is a specific deficit within the orthographic processor that affects the storage and recall of exact letter sequences. This processing speed/orthographic subgroup generally has milder difficulties with reading than students with phonological processing deficits.

Yet another 10-15 percent of poor readers appear to decode words better than they can comprehend the meanings of passages. These poor readers are distinguished from dyslexic poor readers because they can read words accurately and quickly and they can spell. Their problems are caused by disorders of social reasoning, abstract verbal reasoning, or language comprehension.

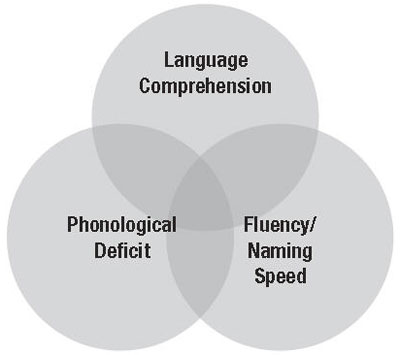

Subtypes of Reading Disability

Researchers currently propose that there are three kinds of developmental reading disabilities that often overlap but that can be separate and distinct:

- Phonological deficit, implicating a core problem in the phonological processing system of oral language.

- Processing speed/orthographic processing deficit, affecting speed and accuracy of printed word recognition (also called naming speed problem or fluency problem).

- Comprehension deficit, often coinciding with the first two types of problems, but specifically found in children with social-linguistic disabilities (e.g., autism spectrum), vocabulary weaknesses, generalized language learning disorders, and learning difficulties that affect abstract reasoning and logical thinking.

If a student has a prominent and specific weakness in either phonological or rapid print (naming-speed) processing, they are said to have a single deficit in word recognition. If they have a combination of phonological and naming-speed deficits, they are said to have a double deficit (Wolf & Bowers, 1999). Double-deficit children are more common than single-deficit and are also the most challenging to remediate. Related and coexisting problems in children with reading disabilities often include:

- faulty pencil grip and letter formation;

- attention problems;

- anxiety;

- task avoidance;

- weak impulse control;

- distractibility;

- problems with comprehension of spoken language; and

- confusion of mathematical signs and computation processes.

About 30 percent of all children with dyslexia also have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Moats, L, & Tolman, C (2009). Excerpted from Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS): The Challenge of Learning to Read (Module 1). Boston: Sopris West.

For more information on Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) visit Voyager Sopris .